It was the month of Jaishta (May-June) in Bengal, and the earth languished under the scorching rays of the sun and sent up a voiceless prayer to the Rain God to come soon and refresh the fields and jungles with the welcome “barsat” (rainy season).

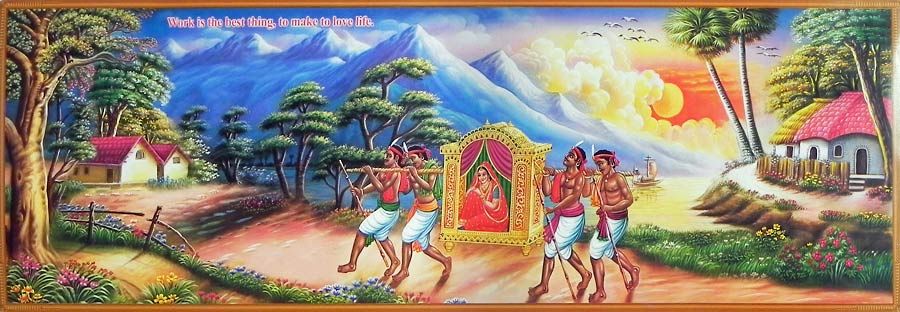

Yet, in spite of the intense heat, a young and delicately nurtured Bengali lady was travelling. She was on her way to pay a visit to her parents-in-law, for after marriage the bride returns to her childhood’s home and remains there, paying visits from time to time to her husband’s home until the day comes when she goes to live there.

It is a Bengali custom that ladies, especially young ladies, must always wear their jewellery, even when travelling. Arms, wrists, neck and ankles, bare of jewels, are a sign of widowhood or dire poverty. Out young heroine was accordingly adorned with jewels and she was also richly attired. Was she not the daughter of a wealthy man and going to visit her mother-in-law? So her mother had lovingly dressed her in an exquisite gold-embroidered Benares silk saree of finest texture and superb workmanship, and the jewellery, which adorned her graceful arms, neck and ankles, was in keeping with the richness of her costume.

Twelve bearers took turns in carrying the covered palanquin or palki in which she travelled. They had been in her father’s service for many years and were known, to be trustworthy. A faithful jhee (maid) accompanied her, sometimes walking beside the palki and at other times sitting within, to fan her young mistress and help to enliven the weary journey with tales of former travels. Two men-servants, whom in Bengal we call durwans and who are permitted to bear arms in defence of their masters’ goods, completed the party. One of them walked on either side of the palanquin and each carried a naked sword in his hand. These two men were tried and trusted retainers of the young lady’s father, and were prepared to defend their master’s daughter even at the cost of their lives.

The route lay through a lonely country district with stretches of rice-fields scattered between, and villages nestling here and there among groves of trees. At one of these villages the party halted awhile for rest and refreshment, and then on again in the fierce heat of a close Indian day.

Thus many miles had been passed; and the evening shades were beginning to cool the wearisome day, when the travellers drew near to a group of trees not far from a small tank (artificial lake). The palki-bearers sighted this ideal resting-place and asked the jhee to inform their young mistress of it, and beseech that they might stop there and refresh themselves with a draught of water, after which they would be able to travel still faster,

A gracious consent was readily given by the fair one within the palanquin. She had found the heat almost beyond endurance, and pitied the bearers who had the weight of her palki and herself added to their sufferings.

The palanquin was gently set down under a large and shady tree, and the durwans respectfully withdrew a little distance to permit of the jhee raising the covering, so that their kind mistress might also enjoy the grateful shade and coolness of the grove.

The spot was lonely and their responsibility great, so the men decided among themselves that they should divide into two parties. Six should remain with the guard to protect their fair charge in case of any untoward happening while the other six refreshed themselves at the lake.

This plan was no sooner agreed upon than the first six trooped off gleefully towards the tank. The others stretched themselves in the shade and relaxed their limbs in the interval of waiting.

Time passed unheeded till it dawned upon some of those who waited that they still thirsted and that the first six seemed too long away. They asked the jhee to obtain leave for them to go and hurry the others up and refresh themselves at the same time, so that the journey might soon be resumed as the evening sun was nearing the horizon, and if they delayed further night would overtake them. The young lady gave the desired permission and the second six soon disappeared towards the tank. They too were long away!

The jhee felt uneasy but kept her fears to herself. Suddenly she too disappeared. Without a word to her mistress she had decided to see what the bearers were doing at the tank. Climbing up a tree, she crept along an overhanging branch and a dreadful sight met her horrified gaze. Some of the bearers lay dead in the shallow water and the surviving ones were fighting desperately for their lives with a small band of outlaws.

Rushing back to the palki with the utmost speed and regardless of onlookers, she flung wide the door, screaming frantically, “Dacoits ! dacoits ! run, didi (elder sister), run. With these eyes of mine I saw them. I climbed a tree and saw them. Some of our bearers lie dead and they are killing the others. Fly ! fly for your life !” With these words she turned and led the way with swiftness impelled by fear.

The lonely occupant of the palanquin received the awful tidings with horror and dismay. Often had she heard tales of dacoits and their ruthless deeds. For a fleeting instant the thought, that she must fall a victim to such desperados, paralysed her with fear; but only for an instant. Her woman’s wit and ingenuity moved her to action. Quickly she divested herself of her heavy jewelled anklets. How could she run thus weighted? and might not their value satisfy the greed of the highwaymen? Flinging them down in the palanquin, she hastily closed the doors and dropped the covering over its sides. Let them think she was within. The search of the palki would delay them awhile.

Then tucking up her rich satee she too started to run for her life. She had gone but a few steps when the voices of the two durwans arrested her. They had heard the jhee’s distracted cry, and their only thought was for their young mistress.

“Didi,” they said, addressing her affectionately and respectfully by the endearing name of sister, which is a custom permitted in Bengal to the servants of every household. In the home of her girlhood a girl is addressed as “didi” (sister) and in her father-in-law’s house as “bow” (son’s wife). Sons of the family are addressed as “dada” (brother, strictly elder brother) and sons-in-law as “jamai”.

“Didi, fear not! As long as there is breath in these bodies we will defend you. If the dacoits overtake us, we will guard you. No harm shall come to you.”

Encouraged by their presence and words, the girl made all possible speed. But her delicate feet were unused to rough, hard roads, and, despite her will and brave efforts, she tripped and stumbled continually. In Bengal, in the hot dry weather, the country roads are difficult to traverse. The deep ruts of the rainy season dry up and the once muddy earth crumbles into thick heavy dust, into which the feet of the wayfarers sink. Fast travelling is difficult even for those who are used to journeying, so the poor young lady made little headway and was soon overtaken by her pursuers. They had not been long in discovering her flight and were soon racing after her from under the tree. As she ran she heard their shouts, and then realised that they had caught up with her guard who were resisting them.

The poor girl ran on and on alone, and presently saw a tiny hamlet hidden among some trees. She made for this as fast as her trembling limbs could carry her and rushed breathlessly into a small red brick-house, the door of which stood slightly ajar, crying: “Shut the door! Dacoits are following me!” Then, overcome with fear and exhaustion, she sank unconscious upon the floor.

The ladies of the little household ran forward on hearing her cry and shut the door promptly. Dacoits were known and feared everywhere. Then they tenderly ministered to the stranger. As soon as she recovered her senses, she related to them what had befallen her and implored their protection.

The master of the house immediately despatched a messenger to a distant police outpost for aid. Soothed and comforted, the girl eagerly hoped and prayed for the arrival of her attendants.

After some time, word was brought in that a palki was approaching. Even in the dark the approach of a palki is made known by the rhythmic cries of the bearers. Soon it arrived in front of the red brick-house and the bearers, halting, asked loudly if a strange lady, richly attired and decked with jewels, was within. From an upper window the master of the house answered them, while the girl and her kindly hostess listened anxiously downstairs. The pseudo palki-bearers next informed the listeners that they were the servants of a very wealthy man and had been conveying his daughter to her parents-in-law’s house.

“But” they boldly declared, “our master’s daughter is such a troublesome girl. She causes us much anxiety whenever she is sent to visit her mother-in-law. She is so unwilling to go that it is with great difficulty that we get her safely there.”

The anxious listeners within felt sure these were the dacoits and longed for the arrival of the police. The disguised thieves persisted in their questioning for some time in spite of the house master’s repeated advice that they had better search elsewhere. At last they departed carrying the palki with them. And the dwellers in the red brick-house breathed more freely. But not for long.

The village was a tiny one and the pretended bearers soon returned from their search. Planting the palki in the doorway, they shouted: “We know for certain that our mistress is hiding somewhere. We feel sure she is in your house. Here we will sit till you send her forth.”

On hearing these words the poor pursued girl fell at the feet of her host, calling herself his daughter and addressing him as “father”, and implored of him not to give her up to these awful dacoits. The good man assured her of his protection while his wife raised her from the floor, and, embracing her, said they would all sooner suffer death than give her up.

The trying hours dragged on till past midnight. Then the dacoits announced that the lady must be produced or they would force an entrance into the house. No reply was given to this ultimatum. The highwaymen waited awhile and then assailed the door with heavy blows.

The distraught girl besought her hostess to take her jewels and hand them out to the burglars and thus ensure peace and safety for all. The mistress of the house declared this would not satisfy the ruffians and once more assured her guest that, whatever happened, they would strive to protect her.

Presently the door gave way and, with coarse oaths and triumphant threats, the dacoits entered. But unknown to them, so busy had they been hammering and swearing, the police had arrived and now followed in on their heels. The dacoits were all captured and confessed their guilt as to the murder of the palki-bearers and the probable death of the two durwans, who, they averred, had fought like tigers.

The bodies of these two devoted servants were found, all battered and bruised, on the roadside and were given honourable cremation by their master, whose daughter they had saved by their devotion.

The jhee was found close to the spot, hiding among the branches of a tree. She had witnessed the fight between the durwans and dacoits and the flight and pursuit of her mistress. When both reached home again, the jhee filled up dull hours with vivid accounts of their adventure. This little story is a true one and shows how difficult and dangerous travel was in the old days in Bengal. Travelling by palki is now in many parts a thing of the past, for the whole Province is being linked together by a network of railways. Good roads and better police arrangements also lessen the terrors of travelling in places where railways are still wanting.