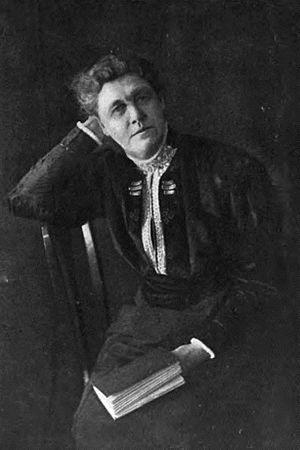

Sir

Francis Galton, FRS ( 1822 – 1911), was an English Victorian era

polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist,

eugenicist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist,

proto-geneticist, and psychometrician. He was knighted in 1909.

Galton

produced over 340 papers and books. He also created the statistical

concept of correlation and widely promoted regression toward the mean.

He was the first to apply statistical methods to the study of human

differences and inheritance of intelligence, and introduced the use of

questionnaires and surveys for collecting data on human communities,

which he needed for genealogical and biographical works and for his

anthropometric studies. He was a pioneer of eugenics, coining the term

itself in 1883, and also coined the phrase "nature versus nurture". His

book Hereditary Genius (1869) was the first social scientific attempt to

study genius and greatness.

As

an investigator of the human mind, he founded psychometrics (the

science of measuring mental faculties) and differential psychology, as

well as the lexical hypothesis of personality. He devised a method for

classifying fingerprints that proved useful in forensic science. He also

conducted research on the power of prayer, concluding it had none due

to its null effects on the longevity of those prayed for. His quest for

the scientific principles of diverse phenomena extended even to the

optimal method for making tea.

As

the initiator of scientific meteorology, he devised the first weather

map, proposed a theory of anticyclones, and was the first to establish a

complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale.

He also invented the Galton Whistle for testing differential hearing

ability. He was Charles Darwin's half-cousin.

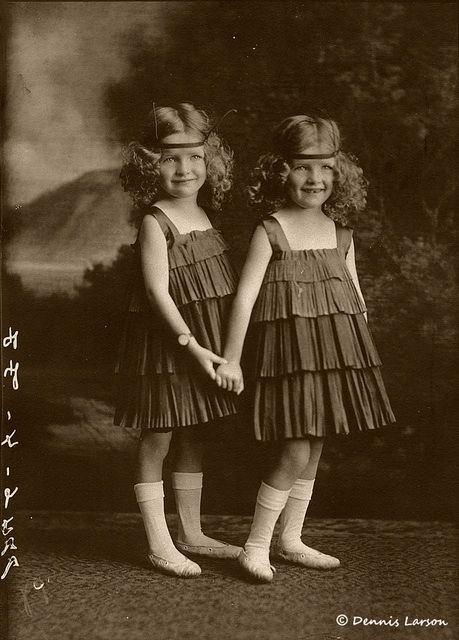

The exceedingly

close resemblance attributed to twins has been the subject of many

novels and plays, and most persons have felt a desire to know upon what

basis of truth those works of fiction may rest. But twins have many

other claims to attention, one of which will be discussed in the present

memoir. It is, that their history affords means of distinguishing

between the effects of tendencies received at birth, and of those that

were imposed by the circumstances of their after lives; in other words,

between the effects of nature and of nurture. This is a subject of

especial importance in its bearings on investigations into mental

heredity, and I, for my part, have keenly felt the difficulty of drawing

the necessary distinction whenever I tried to estimate the degree in

which mental ability was, on the average, inherited. The objection to

statistical evidence in proof of its inheritance has always been: “The

persons whom you compare may have lived under similar social conditions

and have had similar advantages of education, but such prominent

conditions are only a small part of those that determine the future of

each man's life. It is to trifling accidental circumstances that the

bent of his disposition and his success are mainly due, and these you

leave wholly out of account, in fact, they do not admit of being

tabulated, and therefore your statistics, however plausible at first

sight, are really of very little use.” No method of enquiry which I have

been able to carry out, and I have tried many methods, is wholly free

from this objection. I have therefore attacked the problem from the

opposite side, seeking for some new method by which it would be possible

to weigh in just scales the respective effects of nature and nurture,

and to ascertain their several shares in framing the disposition and

intellectual ability of men. The life history of twins supplies what I

wanted. We might begin by enquiring about twins who were closely alike

in boyhood and youth, and who were educated together for many years, and

learn whether they subsequently grew unlike, and, if so, what the main

causes were which, in the opinion of the family, produced the

dissimilarity. In this way we may obtain much direct evidence of the

kind we want; but we can also obtain yet more valuable evidence by a

converse method. We can enquire into the history of twins who were

exceedingly unlike in childhood, and learn how far they became

assimilated under the influence of their identical nurtures; having the

same home, the same teachers, the same associates, and in every other

respect the same surroundings.

My materials were

obtained by sending circulars of enquiry to persons who were either

twins themselves or the near relations of twins. The printed questions

were in thirteen groups; the last of them asked for the addresses of

other twins known to the recipient who might be likely to respond if I

wrote to them. This happily led to a continually widening circle of

correspondence, which I pursued until enough material was accumulated

for a general reconnaissance of the subject.

The reader will

easily understand that the word “twins” is a vague expression, which

covers two very dissimilar events; the one corresponding to the progeny

of animals that have usually more than one young one at a birth, and the

other corresponding to those double-yolked eggs that are due to two

germinal spots in a single ovum. The consequence of this is, that I find

a curious discontinuity in my results. One would have expected that

twins would commonly be found to possess a certain average likeness to

one another; that a few would greatly exceed that degree of likeness,

and a few would greatly fall short of it; but this is not at all the

case. Twins may be divided into three groups, so distinct that there are

not many intermediate instances; namely, strongly alike, moderately

alike, and extremely dissimilar. When the twins are a boy and a girl,

they are never closely alike; in fact, their origin never corresponds to

that of the above-mentioned double-yolked eggs.

I have received

about eighty returns of cases of close similarity, thirty-five of which

entered into many instructive details. In a few of these not a single

point of difference could be specified. In the remainder, the colour of

the hair and eyes were almost always identical; the height, weight, and

strength were generally very nearly so, but I have a few cases of a

notable difference in these, notwithstanding the resemblance was

otherwise very near. The manner and address of the thirty-five pairs of

twins is usually described as being very similar, though there often

exists a difference of expression familiar to near relatives but

unperceived by strangers. The intonation of the voice when speaking is

commonly the same, but it frequently happens that the twins sing in

different keys. Most singularly, that one point in which similarity is

rare is the handwriting. I cannot account for this, considering how

strongly handwriting runs in families, but I am sure of the fact. I have

only one case in which nobody, not even the twins themselves, could

distinguish their own notes of lectures, etc.; barely two or three in

which the handwriting was undistinguishable by others, and only a few in

which it was described as closely alike. On the other hand, I have many

in which it is stated to be unlike, and some in which it is alluded to

as the only point of difference.

One of my enquiries

was for anecdotes as regards the mistakes made by near relatives between

the twins. They are numerous, but not very varied in character. When

the twins are children, they have commonly to be distinguished by

ribbons tied round their wrist or neck; nevertheless the one is

sometimes fed, physicked, and whipped by mistake for the other, and the

description of these little domestic catastrophes is usually given to me

by the mother, in a phraseology that is somewhat touching by reason of

its seriousness. I have one case in which a doubt remains whether the

children were not changed in their bath, and the presumed A is not

really B, and vice versa. In another case an artist was engaged on the

portraits of twins who were between three and four years of age; he had

to lay aside his work for three weeks, and, on resuming it, could not

tell to which child the respective likenesses he had in hand belonged.

The mistakes are less numerous on the part of the mother during the

boyhood and girlhood of the twins, but almost as frequent on the part of

strangers. I have many instances of tutors being unable to distinguish

their twin pupils. Thus, two girls used regularly to impose on their

music teacher when one of them wanted a whole holiday; they had their

lessons at separate hours, and the one girl sacrificed herself to

receive two lessons on the same day, while the other one enjoyed

herself. Here is a brief and comprehensive account: “Exactly alike in

all, their schoolmasters never could tell them apart; at dancing parties

they constantly changed partners without discovery; their close

resemblance is scarcely diminished by age.” The following is a typical

schoolboy anecdote: Two twins were fond of playing tricks, and

complaints were frequently made; but the boys would never own which was

the guilty one, and the complainants were never certain which of the two

he was. One head master used to say he would never flog the innocent

for the guilty, and another used to flog both. No less than nine

anecdotes have reached me of a twin seeing his or her reflection in a

looking-glass, and addressing it, in the belief it was the other twin in

person. I have many anecdotes of mistakes when the twins were nearly

grown up. Thus: “Amusing scenes occurred at college when one twin came

to visit the other; the porter on one occasion refused to let the

visitor out of the college gates, for, though they stood side by side,

he professed ignorance as to which he ought to allow to depart.”

Children are usually

quick in distinguishing between their parents and his or her twin: but I

have two cases to the contrary. Thus, the daughter of a twin says:

“Such was the marvellous similarity of their features, voice, manner,

etc. that I remember, as a child, being very much puzzled, and I think,

had my aunt lived much with us, I should have ended by thinking I had

two mothers.” The other, a father of twins, remarks: “We were extremely

alike, and are so at this moment, so much so that our children up to

five and six years old did not know us apart.”

I have four or five

instances of doubt during an engagement of marriage. Thus: “A married

first, but both twins met the lady together for the first time, and fell

in love with her there and then. A managed to see her home and to gain

her affection, though B went sometimes courting in his place, and

neither the lady nor her parents could tell which was which.” I have

also a German letter, written in quaint terms, about twin brothers who

married sisters, but could not easily be distinguished by them. In the

well-known novel by Mr. Wilkie Collins of “Poor Miss Finch,” the blind

girl distinguishes the twin she loves by the touch of his hand, which

gives her a thrill that the touch of the other brother does not.

Philosophers have not, I believe, as yet investigated the conditions of

such thrills; but I have a case in which Miss Finch's test would have

failed. Two persons, both friends of a certain twin lady, told me that

she had frequently remarked to them that “kissing her twin sister was

not like kissing her other sisters, but like kissing herself, her own

hand, for example.”

It would be an

interesting experiment for twins who were closely alike, to try how far

dogs could distinguish between them by scent.

I have a few

anecdotes of strange mistakes made between twins in adult life. Thus, an

officer writes: “On one occasion when I returned from foreign service

my father turned to me and said, 'I thought you were in London,'

thinking I was my brother, yet he had not seen me for nearly four years,

our resemblance was so great.”

The next and last

anecdote I shall give is, perhaps, the most remarkable of those that I

have: it was sent me by the brother of the twins, who were in middle

life at the time of its occurrence: “A was again coming home from India,

on leave; the ship did not arrive for some days after it was due; the

twin brother B had come up from his quarters to receive A, and their old

mother was very nervous. One morning A rushed in, saying, 'Oh, mother,

how are you?' Her answer was, 'No, B, it's a bad joke; you know how

anxious I am!' and it was a little time before A could persuade her that

he was the real man.”

Enough has been said

to prove that an extremely close personal resemblance frequently exists

between twins of the same sex; and that, although the resemblance

usually diminishes as they grow into manhood and womanhood, some cases

occur in which the resemblance is lessened in a hardly perceptible

degree. It must be borne in mind that the divergence of development,

when it occurs, need not be ascribed to the effect of different

nurtures, but that it is quite possible that it may be due to the

appearance of qualities inherited at birth, though dormant, like gout,

in early life. To this I shall recur.

There is a curious

feature in the character of the resemblance between twins, which has

been alluded to by a few correspondents: it is well illustrated by the

following quotations. A mother of twins says: “There seems to be a sort

of interchangeable likeness in expression, that often gave to each the

affect of being more like his brother than himself.” Again, two twin

brothers, writing to me, after analysing their points of resemblance,

which are close and numerous, and pointing out certain shades of

difference, add: “These seem to have marked us through life, though for a

while when we were first separated, the one to go to business, and the

other to college, our respective characters were inverted; we both think

that at that time we each ran into the character of the other. The

proof of this consists in our own recollections, in our correspondence

by letter, and in the views which we then took of matters in which we

were interested.” In explanation of this apparent interchangeableness,

we must recollect that no character is simple, and that in twins who

strongly resemble each other every expression in the one may be matched

by a corresponding expression in the other, but it does not follow that

the same expression should be the dominant one in both cases. Now it is

by their dominant expressions that we should distinguish between the

twins; consequently when one twin has temporarily the expression which

is the dominant one in his brother, he is apt to be mistaken for him.

There are also cases where the development of the two twins is not

strictly by equal steps; they reach the same goal at the same time, but

not by identical stages. Thus: A is born the larger, then B overtakes

and surpasses A, the end being that the twins become closely alike. This

process would aid in giving an interchangeable likeness at certain

periods of their growth, and is undoubtedly due to nature more

frequently than to nurture.

Among my thirty-five

detailed cases of close similarity, there are no less than seven in

which both twins suffered from some special ailment or had some

exceptional peculiarity. One twin writes that she and her sister “have

both the defect of not being able to come down stairs quickly, which,

however, was not born with them, but came on at the age of twenty.”

Another pair of twins have a slight congenital flexure of one of the

joints of the little finger: it was inherited from a grandmother, but

neither parents, nor brothers, nor sisters show the least trace of it.

In another case, one was born ruptured, and the other became so at six

months old. Two twins at the age of twenty-three were attacked by

toothache, and the same tooth had to be extracted in each case. There

are curious and close correspondences mentioned in the falling off of

the hair. Two cases are mentioned of death from the same disease; one of

which is very affecting. The outline of the story was that the twins

were closely alike and singularly attached, and had identical tastes;

they both obtained Government clerkships, and kept house together, when

one sickened and died of Bright's disease, and the other also sickened

of the same disease and died seven months later.

In no less than nine

out of the thirty-five cases does it appear that both twins are apt to

sicken at the same time. This implies so intimate a constitutional

resemblance, that it is proper to give some quotations in evidence.

Thus, the father of two twins says: “Their general health is closely

alike; whenever one of them has an illness the other invariably has the

same within a day or two, and they usually recover in the same order.

Such has been the case with whooping cough, chicken-pox, and measles;

also with slight bilious attacks, which they have successively.

Latterly, they had a feverish attack at the same time.” Another parent

of twins says: “If anything ails one of them, identical symptoms nearly

always appear in the other: this has been singularly visible in two

instances during the last two months. Thus, when in London, one fell ill

with a violent attack of dysentery, and within twenty-four hours the

other had precisely the same symptoms.”

A medical man writes

of twins with whom he is well acquainted: “Whilst I knew them, for a

period of two years, there was not the slightest tendency towards a

difference in body or mind; external influences seemed powerless to

produce any dissimilarity.” The mother of two other twins, after

describing how they were ill simultaneously up to the age of fifteen,

adds, that they shed their first milk teeth within a few hours of each

other.

Trousseau has a very

remarkable case (in the chapter on Asthma) in his important work,

“Clinique Médicale.” It was quoted at length in the original French in

Mr. Darwin's “Variation Under Domestication,” - The following is a

translation:

“I attended twin

brothers so extraordinarily alike, that it was impossible for me to tell

which was which without seeing them side by side. But their physical

likeness extended still deeper for they had, so to speak, a yet more

remarkable pathological resemblance. Thus, one of them, whom I saw at

the Néothermes at Paris, suffering from rheumatic ophthalmia, said to

me, 'At this instant, my brother must be having an ophthalmia like

mine;' and, as I had exclaimed against such an assertion, he showed me a

few days afterwards a letter just received by him from his brother, who

was at that time at Vienna, and who expressed himself in these words:

'I have my ophthalmia; you must be having yours.' However singular this

story may appear, the fact is none the less exact: it has not been told

to me by others, but I have seen it myself; and I have seen other

analogous cases in my practice. These twins were also asthmatic, and

asthmatic to a frightful degree. Though born in Marseilles, they never

were able to stay in that town, where their business affairs required

them to go, without having an attack. Still more strange, it was

sufficient for them to get away only as far as Toulon in order to be

cured of the attack caught at Marseilles. They travelled continually,

and in all countries, on business affairs, and they remarked that

certain localities were extremely hurtful to them, and that in others

they were free from all asthmatic symptoms.”

I do not like to

pass over here a most dramatic tale in the Psychologie Morbide of Dr. J.

Moreau (de Tours), Médecin de l'Hospice de Bicetre. Paris, 1859 - . He

speaks “of two twin brothers who had been confined, on account of

monomania, at Bicetre.... Physically the two young men are so nearly

alike that the one is easily mistaken for the other. Morally, their

resemblance is no less complete, and is most remarkable in its details.

Thus, their dominant ideas are absolutely the same. They both consider

themselves subject to imaginary persecutions; the same enemies have

sworn their destruction, and employ the same means to effect it. Both

have hallucinations of hearing. They are both of them melancholy and

morose; they never address a word to anybody, and will hardly answer the

questions that others address to them. They always keep apart and never

communicate with one another. An extremely curious fact which has been

frequently noted by the superintendents of their section of the

hospital, and by myself, is this: From time to time, at very irregular

intervals of two, three, and many months, without appreciable cause, and

by the purely spontaneous effect of their illness, a very marked change

takes place in the condition of the two brothers. Both of them, at the

same time, and often on the same day, rouse themselves from their

habitual stupor and prostration; they make the same complaints, and they

come of their own accord to the physician, with an urgent request to be

liberated. I have seen this strange thing occur, even when they were

some miles apart, the one being at Bicetre and the other living at

Sainte-Anne.”

Dr. Moreau ranked as

a very considerable medical authority, but I cannot wholly accept this

strange story without fuller information. Dr. Moreau writes it in too

off-hand a way to carry the conviction that he had investigated the

circumstances with the sceptic spirit and scrupulous exactness which so

strange a phenomenon would have required. If full and precise notes of

the case exist, they certainly ought to be published at length. I sent a

copy of this passage to the principal authorities among the physicians

to the insane in England, asking if they had ever witnessed any similar

case. In reply, I have received three noteworthy instances, but none to

be compared in their exact parallelism with that just given. The details

of these three cases are painful, and it is not necessary to my general

purpose that I should further allude to them.

There is another

curious French case of insanity in twins, which was pointed out to me by

Professor Paget, described by Dr. Baume in the Annales

Medico-Psychologiques, - of which the following is an abstract. The

original contains a few more details, but it is too long to quote:

Francois and Martin, fifty years of age, worked as railroad contractors

between Quimper and Châteaulin. Martin had twice had slight attacks of

insanity. On January 15, a box in which the twins deposited their

savings was robbed. On the night of January 23-4 both Francois (who

lodged at Quimper) and Martin (who lived with his wife and children at

St. Lorette, two leagues from Quimper) had the same dream at the same

hour, three A. M., and both awoke with a violent start, calling out, “I

have caught the thief! I have caught the thief! they are doing injury to

my brother!” They were both of them extremely agitated, and gave way to

similar extravagances, dancing and leaping. Martin sprang on his

grandchild, declaring that he was the thief, and would have strangled

him if he had not been prevented: he then became steadily worse,

complained of violent pains in his head, went out of doors on some

excuse, and tried to drown himself in the River Steir, but was forcibly

stopped by his son, who had watched and followed him. He was then taken

to an asylum by gendarmes, where he died in three days. Francois, on his

part calmed down on the morning of the 24th, and employed the day in

enquiring about the robbery. By a strange chance he crossed his

brother's path at the moment when the latter was struggling with the

gendarmes; then he himself became maddened, giving way to extravagant

gestures and making incoherent proposals (similar to those of his

brother). He then asked to be bled, which was done, and afterwards,

declaring himself to be better, went out on the pretext of executing

some commission, but really to drown himself in the River Steir, which

he actually did, at the very spot where Martin had attempted to do the

same thing a few hours previously.

The next point which

I shall mention, in illustration of the extremely close resemblance

between certain twins, is the similarity in the association of their

ideas. No less than eleven out of the thirty-five cases testify to this.

They make the same remarks on the same occasion, begin singing the same

song at the same moment, and so on; or one would commence a sentence,

and the other would finish it. An observant friend graphically described

to me the effect produced on her by two such twins whom she had met

casually. She said: “Their teeth grew alike, they spoke alike and

together, and said the same things, and seemed just like one person.”

One of the most curious anecdotes that I have received concerning this

similarity of ideas was that one twin A, who happened to be at a town in

Scotland, bought a set of champagne glasses which caught his attention,

as a surprise for his brother B; while at the same time, B, being in

England, bought a similar set of precisely the same pattern as a

surprise for A. Other anecdotes of a like kind have reached me about

these twins.

The last point to

which I shall allude regards the tastes and dispositions of the

thirty-five pairs of twins. In sixteen cases - that is, in nearly one

half of them - these were described as closely similar; in the remaining

nineteen they were much alike, but subject to certain named

differences. These differences belonged almost wholly to such groups of

qualities as these: The one was the more vigorous, fearless, energetic;

the other was gentle, clinging, and timid: or, again, the one was more

ardent, the other more calm and gentle; or again, the one was the more

independent, original, and self-contained; the other the more generous,

hasty, and vivacious. In short the difference was always that of

intensity or energy in one or other of its protean forms: it did not

extend more deeply into the structure of the characters. The more

vivacious might be subdued by ill health, until he assumed the character

of the other; or the latter might be raised by excellent health to that

of the former. The difference is in the key-note, not in the melody.

It follows from what

has been said concerning the similar dispositions of the twins, the

similarity in the associations of their ideas, of their special

ailments, and of their illnesses generally, that the resemblances are

not superficial, but extremely intimate. I have only two cases

altogether of a strong bodily resemblance being accompanied by mental

diversity, and one case only of the converse kind. It must be remembered

that the conditions which govern extreme likeness between twins are not

the same as those between ordinary brothers and sisters (I may have

hereafter to write further about this); and that it would be wholly

incorrect to generalize from what has just been said about the twins,

that mental and bodily likeness are invariably co-ordinate; such being

by no means the case.

We are now in a

position to understand that the phrase “close similarity” is no

exaggeration, and to realize the value of the evidence about to be

adduced. Here are thirty-five cases of twins who were “closely alike” in

body and mind when they were young, and who have been reared exactly

alike up to their early manhood and womanhood. Since then the conditions

of their lives have changed; what change of conditions has produced the

most variation?

It was with no

little interest that I searched the records of the thirty-five cases for

an answer; and they gave an answer that was not altogether direct, but

it was very distinct, and not at all what I had expected. They showed me

that in some cases the resemblance of body and mind had continued

unaltered up to old age, notwithstanding very different conditions of

life; and they showed in the other cases that the parents ascribed such

dissimilarity as there was wholly, or almost wholly, to some form of

illness. In four cases it was scarlet fever; in one case, typhus; in

one, a slight effect was ascribed to a nervous fever: then I find

effects from an Indian climate; from an illness (unnamed) of nine

months' duration; from varicose veins; from a bad fracture of the leg,

which prevented all active exercise afterwards; and there were three

other cases of ill health. It will be sufficient to quote one of the

returns; in this the father writes:

“At birth they were

exactly alike, except that one was born with a bad varicose affection,

the effect of which had been to prevent any violent exercise, such as

dancing, or running, and, as she has grown older, to make her more

serious and thoughtful. Had it not been for this infirmity, I think the

two would have been as exactly alike as it is possible for two women to

be, both mentally and physically; even now they are constantly mistaken

for one another.”

In only a very few

cases is there some allusion to the dissimilarity being partly due to

the combined action of many small influences, and in no case is it

largely, much less wholly, ascribed to that cause. In not a single

instance have I met with a word about the growing dissimilarity being

due to the action of the firm, free will of one or both of the twins,

which had triumphed over natural tendencies; and yet a large proportion

of my correspondents happen to be clergymen whose bent of mind is

opposed, as I feel assured from the tone of their letters, to a

necessitarian view of life.

It has been remarked

that a growing diversity between twins may be ascribed to the tardy

development of naturally diverse qualities; but we have a right, upon

the evidence I have received, to go further than this. We have seen that

a few twins retain their close resemblance through life; in other

words, instances do exist of thorough similarity of nature, and in these

external circumstances do not create dissimilarity. Therefore, in those

cases, where there is a growing diversity, and where no external cause

can be assigned either by the twins themselves or by their family for

it, we may feel sure that it must be chiefly or altogether due to a want

of thorough similarity in their nature. Nay further, in some cases it

is distinctly affirmed that the growing dissimilarity can be accounted

for in no other way. We may therefore broadly conclude that the only

circumstance, within the range of those by which persons of similar

conditions of life are affected, capable of producing a marked effect on

the character of adults, is illness or some accident which causes

physical infirmity. The twins who closely resembled each other in

childhood and early youth, and were reared under not very dissimilar

conditions, either grow unlike through the development of natural

characteristics which had lain dormant at first, or else they continue

their lives, keeping time like two watches, hardly to be thrown out of

accord except by some physical jar. Nature is far stronger than nurture

within the limited range that I have been careful to assign to the

latter.

The effect of

illness, as shown by these replies, is great, and well deserves further

consideration. It appears that the constitution of youth is not so

elastic as we are apt to think, but that an attack, say of scarlet

fever, leaves a permanent mark, easily to be measured by the present

method of comparison. This recalls an impression made strongly on my

mind several years ago by the sight of a few curves drawn by a

mathematical friend. He took monthly measurements of the circumference

of his children's heads during the first few years of their lives, and

he laid down the successive measurements on the successive lines of a

piece of ruled paper, by taking the edge of the paper as a base. He then

joined the free ends of the lines, and so obtained a curve of growth.

These curves had, on the whole, that regularity of sweep that might have

been expected, but each of them showed occasional halts, like the

landing places on a long flight of stairs. The development had been

arrested by something, and was not made up for by after growth. Now, on

the same piece of paper my friend had also registered the various

infantile illnesses of the children, and corresponding to each illness

was one of these halts. There remained no doubt in my mind that, if

these illnesses had been warped off, the development of the children

would have been increased by almost the precise amount lost in these

halts. In other words, the disease had drawn largely upon the capital,

and not only on the income, of their constitutions. I hope these remarks

may induce some men of science to repeat similar experiments on their

children of the future. They may compress two years of a child's history

on one side of a ruled half-sheet of foolscap paper if they cause each

successive line to stand for a successive month, beginning from the

birth of the child; and if they mark off the measurements by laying, not

the 0-inch division of the tape against the edge of the pages, but,

say, the 10-inch division - in order to economize space.

The steady and

pitiless march of the hidden weaknesses in our constitutions, through

illness to death, is painfully revealed by these histories of twins. We

are too apt to look upon illness and death as capricious events, and

there are some who ascribe them to the direct effect of supernatural

interference, whereas the fact of the maladies of two twins being

continually alike, shows that illness and death are necessary incidents

in a regular sequence of constitutional changes, beginning at birth,

upon which external circumstances have, on the whole, very small effect.

In cases where the maladies of the twins are continually alike, the

clock of life moves regularly on, governed by internal mechanism. When

the hand approaches the hour mark, there is a sudden click, followed by a

whirling of wheels; at the culminating moment, the stroke falls.

Necessitarians may derive new arguments from the life histories of

twins.

We will now consider

the converse side of our subject. Hitherto we have investigated cases

where the similarity at first was close, but afterwards became less: now

we will examine those in which there was great dissimilarity at first,

and will see how far an identity of nurture in childhood and youth

tended to assimilate them. As has been already mentioned, there is a

large proportion of cases of sharply contrasted characteristics, both of

body and mind, among twins. I have twenty such cases, given with much

detail. It is a fact, that extreme dissimilarity, such as existed

between Esau and Jacob, is a no less marked peculiarity in twins of the

same sex, than extreme similarity. On this curious point, and on much

else in the history of twins, I have many remarks to make, but this is

not the place to make them.

The evidence given

by the twenty cases above mentioned is absolutely accordant, so that the

character of the whole may be exactly conveyed by two or three

quotations. One parent says: “They have had exactly the same nurture

from their birth up to the present time; they are both perfectly healthy

and strong, yet they are otherwise as dissimilar as two boys could be,

physically, mentally, and in their emotional nature. ” Here is another

case: “I can answer most decidedly that the twins have been perfectly

dissimilar in character, habits, and likeness from the moment of their

birth to the present time, though they were nursed by the same woman,

went to school together, and were never separated till the age of

fifteen.” Here again is one more, in which the father remarks: “They

were curiously different in body and mind from their birth.” The

surviving twin (a senior wrangler of Cambridge) adds: “A fact struck all

our school contemporaries, that my brother and I were complementary, so

to speak, in point of ability and disposition. He was contemplative,

poetical, and literary to a remarkable degree, showing great power in

that line. I was practical, mathematical, and linguistic. Between us we

should have made a very decent sort of a man.” I could quote others just

as strong as these, while I have not a single case in which my

correspondents speak of originally dissimilar characters having become

assimilated through identity of nurture. The impression that all this

evidence leaves on the mind is one of some wonder whether nurture can do

anything at all beyond giving instruction and professional training. It

emphatically corroborates and goes far beyond the conclusions to which

we had already been driven by the cases of similarity. In these, the

causes of divergence began to act about the period of adult life, when

the characters had become somewhat fixed; but here the causes conducive

to assimilation began to act from the earliest moment of the existence

of the twins, when the disposition was most pliant, and they were

continuous until the period of adult life. There is no escape from the

conclusion that nature prevails enormously over nurture when the

differences of nurture do not exceed what is commonly to be found among

persons of the same rank of society and in the same country. My only

fear is that my evidence seems to prove too much and may be discredited

on that account, as it seems contrary to all experience that nurture

should go for little. But experience is often fallacious in ascribing

great effects to trifling circumstances. Many a person has amused

himself with throwing bits of stick into a tiny brook and watching their

progress; how they are arrested, first by one chance obstacle, then by

another; and again, how their onward course is facilitated by a

combination of circumstances. He might ascribe much importance to each

of these events, and think how largely the destiny of the stick has been

governed by a series of trifling accidents. Nevertheless all the sticks

succeed in passing down the current, and they travel, in the long run,

at nearly the same rate. So it is with life in respect to the several

accidents which seem to have had a great effect upon our careers. The

one element, which varies in different individuals, but is constant in

each of them, is the natural tendency; it corresponds to the current in

the stream, and invariably asserts itself. More might be added on this

matter, and much might be said in qualification of the broad conclusions

to which we have arrived, as to the points in which education appears

to create the most permanent effect; how far by training the intellect

and how far by subjecting the boy to a higher or lower tone of public

opinion; but this is foreign to my immediate object. The latter has been

to show broadly, and, I trust, convincingly, that statistical

estimation of natural gifts by a comparison of successes in life, is not

open to the objection stated at the beginning of this memoir. We have

only to take reasonable care in selecting our statistics, and then we

may safely ignore the many small differences in nurture which are sure

to have characterized each individual case.