Showing posts with label QUOTES. Show all posts

Showing posts with label QUOTES. Show all posts

Thursday, October 22, 2020

PALIMPSEST - by Catherynne M. Valente

HAPPINESS AND CONTEMPLATION - by Josef Pieper

SOLITUDE - by Ester Buchholz

Monday, July 27, 2020

FUNNY QUOTES

1. Do not forget to throw garbage ...

out of a bucket ... out of your head ...

out of life!

2. When your affairs go badly -

just do not go with them.

3. The best teacher in life is experience.

It takes, however, expensively,

but explains intelligibly.

4. If the error can be corrected, then you

have not made a mistake.

5. Thanks to those people who entered

my life and made it beautiful. And yet,

thanks to those people who came out of it

\and made it even better.

6. There will always be someone who

does not like what you do. This is

normal. Everyone likes kittens in a row.

7. If someone swears at you, gets angry

or offended - crush him with

your positive.

8. You must arrange your life until life

begins to suit you.

9. I do not want to upset you,

but I'm fine!

10. I do not step on a rake.

I already dance on them!

11. The recipe for youth: rejoice at every

little thing and don’t be nervous

about every bastard.

12. The best day is today!

|

Monday, June 15, 2020

CHATEAUBRIAND - Memoirs From Beyond the Grave

The "Mémoires d' Outre-Tombe," which was partly published before Chateaubriand's death, represents a work spread over a great part of Chateaubriand's life, and reveals as no other of his books the innermost personality of the man.

I. -YOUTH AND ITS FOLLIES

Four years ago, on my return from the Holy Land, I purchased a little country house, situated near the hamlet of Aulnay, in the vicinity of Sceaux and Chatenay. The house is in a valley, encircled by thickly wooded hills. The ground attached to this habitation is a sort of wild orchard. These narrow confines seem to me to be fitting boundaries of my long-protracted hopes. I have selected the trees, as far as I was able, from the various climes I have visited. They remind me of my wanderings.

Knight-errant as I am, I have the sedentary tastes of a monk. It was here I wrote the "Martyrs," the "Abencerrages," the "Itinéraire," and "Moise." To what shall I devote myself in the evenings of the present autumn? This day, October 4, being the anniversary of my entrance into Jerusalem, tempts me to commence the history of my life.

I am of noble descent, and I have profited by the accident of my birth, inasmuch as I have retained that firm love of liberty which characterises the members of an aristocracy whose last hour has sounded. Aristocracy has three successive ages, the age of superiority, the age of privilege, and the age of vanity. Having emerged from the first age, ft degenerates in the second age, and perishes in the third.

When I was a young man, and learned the meaning of love, I was a mystery to myself. All my days were adieux. I could not see a woman without being troubled. I blushed if one spoke to me. My timidity, already excessive towards everyone, became so great with a woman that I would have preferred any torment whatsoever to that of remaining alone with one. She was no sooner gone than I would have recalled her with all my heart. Had anyone delivered to me the most beautiful slaves of the seraglio, I should not have known what to say to them. Accident enlightened me.

Had I done as other men do, I should sooner have learned the pleasures and pains of passion, the germ of which I carried in myself; but everything in me assumed an extraordinary character. The warmth of imagination, my bashfulness and solitude, caused me to turn back upon myself. For want of a real object, by the power of my vague desires, I evoked a phantom which never quitted me more. I know not whether the history of the human heart furnishes another example of this kind.

I pictured then to myself an ideal beauty, moulded from the various charms of all the women I had seen. I gave her the eyes of one young village girl, and the rosy freshness of another. This invisible enchantress constantly attended me; I communed with her as with a real being. She varied at the will of my wandering fancy. Now she was Diana clothed in azure, now Aphrodite unveiled, now Thalia with her laughing mask, now Hebe bearing the cup of eternal youth.

A young queen approaches, brilliant with diamonds and flowers, this was always my sylph. She seeks me at midnight, amidst orange groves, in the corridors of a palace washed by the waves, on the balmy shore of Naples or Messina; the light sound of her footsteps on the mosaic floor mingles with the scarcely heard murmur of the waves.

Awaking from these my dreams, and finding myself a poor little obscure Breton, who would attract the eyes of no one, despair seized upon me. I no longer dared to raise my eyes to the brilliant phantom which I had attached to my every step. This delirium lasted for two whole years. I spoke little; my taste for solitude redoubled. I showed all the symptoms of a violent passion. I was absent, sad, ardent, savage. My days passed on in wild, extravagant, mad fashion, which nevertheless had a peculiar charm.

I have now reached a period at which I require some strength of mind to confess my weakness. I had a gun, the worn-out trigger of which often went off unexpectedly. I loaded this gun with three balls, and went to a spot at a considerable distance from the great Mall. I cocked the gun, put the end of the barrel into my mouth, and struck the butt-end against the ground. I repeated the attempt several times, but unsuccessfully. The appearance of a gamekeeper interrupted me in my design. I was a fatalist, though without my own intention or knowledge. Supposing that my hour was not yet come, I deferred the execution of my project to another day.

Any whose minds are troubled by these delineations should remember that they are listening to the voice of one who has passed from this world. Reader, whom I shall never know, of me there is nothing, nothing but what I am in the hands of the living God.

A few weeks later I was sent for one morning. My father was waiting for me in his cabinet.

"Sir," said he, "you must renounce your follies. Your brother has obtained for you a commission as ensign in the regiment of Navarre. You must presently set out for Rennes, and thence to Cambray. Here are a hundred louis-d'or; take care of them. I am old and ill, I have no long time to live. Behave like a good man, and never dishonour your name."

He embraced me. I felt the hard and wrinkled face pressed with emotion against mine. This was my father's last embrace.

The mail courier brought me to my garrison. Having joined the regiment in the garb of a citizen, twenty four hours afterwards I assumed that of a soldier; it appeared as if I had worn it always. I was not fifteen days in the regiment before I became an officer. I learned with facility both the exercise and the theory of arms. I passed through the offices of corporal and sergeant with the approbation of my instructors. My rooms became the rendezvous of the old captains, as well as of the young lieutenants.

The same year in which I went through my first training in arms at Cambray brought news of the death of Frederic II. I am now ambassador to the nephew of this great king, and write this part of my memoirs in Berlin. This piece of important public news was succeeded by another, mournful to me. It was announced to me that my father had been carried off by an attack of apoplexy.

I lamented M. de Chateaubriand. I remembered neither his severity nor his weakness. If my father's affection for me partook of the severity of his character, in reality it was not the less deep. My brother announced to me that I had already obtained the rank of captain of cavalry, a rank entitling me to honour and courtesy.

A few days later I set out to be presented at the first court in Europe. I remember my emotion when I saw the king at Versailles. When the king's levée was announced, the persons not presented withdrew. I felt an emotion of vanity; I was not proud of remaining, but I should have felt humiliated at having to retire. The royal bed-chamber door opened; I saw the king, according to custom, finishing his toilet. He advanced, on his way to the chapel, to hear mass. I bowed, Marshal de Duras announcing my name: "Sire, le Chevalier de Chateaubriand."

The king graciously returned my salutation, and seemed to wish to address me; but, more embarrassed than I, finding nothing to say to me, he passed on. This sovereign was Louis XVI., only six years before he was brought to the scaffold.

II. IN THE YEARS OF REVOLUTION

My political education was begun by my residence, at different times, in Brittany in the years 1787 and 1788. The states of this province furnished the model of the States-General; and the particular troubles which broke out in the provinces of Brittany and Dauphiny were the forerunners of those of the nation at large.

The change which had been developing for two hundred years was then reaching its limits. France was rapidly tending to a representative system by means of a contest of the magistracy with the royal power.

The year 1789, famous in the history of France, found me still on the plains of my native Brittany. I could not leave the province till late in the year, and did not reach Paris till after the pillage of the Maison Reveillon, the opening of the States-General, the constitution of the Tièrs-État in the National Assembly, the oath of the Jeu-de-Paume, the royal council of the 23rd of June, and the junction of the clergy and nobility in the Tièrs-État. The court, now yielding, now attempting to resist, allowed itself to be browbeaten by Mirabeau.

The counter-blow to that struck at Versailles was felt at Paris. On July 14 the Bastille was taken. I was present as a spectator at this event. If the gates had been kept shut the fortress would never have been taken. De Launay, dragged from his dungeon, was murdered on the steps of the Hôtel de Ville. Flesselles, the prevôt des marchands, was shot through the head. Such were the sights delighted in by heartless saintly hypocrites. In the midst of these murders the people abandoned themselves to orgies similar to those carried on in Rome during the troubles under Otto and Vitellius. The monarchy was demolished as rapidly as the Bastille in the sitting of the National Assembly on the evening of August 4.

My regiment, quartered at Rouen, preserved its discipline for some time. But at length insurrection broke out among the soldiers in Navarre. The Marquis de Mortemar emigrated; the officers followed him. I had neither adopted nor rejected the new opinions; I neither wished to emigrate nor to continue my military career. I therefore retired, and I decided to go to America.

I sailed for that land, and my heart beat when we sighted the American coast, faintly traced by the tops of some maple-trees emerging, as it were, from the sea. A pilot came on board and we sailed into the Chesapeake and soon set foot on American soil.

At that time I had a great admiration for republics, though I did not believe them possible in our era of the world. My idea of liberty pictured her such as she was among the ancients, daughter of the manners of an infant society. I knew her not as the daughter of enlightenment and the civilisation of centuries; as the liberty whose reality the representative republic has proved God grant it may be durable! We are no longer obliged to work in our own little fields, to curse arts and sciences, if we would be free.

I met General Washington. He was tall, calm, and cold rather than noble in mien; the engravings of him are good. We sat down, and I explained to him as well as I could the motive of my journey. He answered me in English and French monosyllables, and listened to me with a sort of astonishment. I perceived this, and said to him with some warmth: "But is it less difficult to discover the north-west passage than to create a nation as you have done?"

"Well, well, young man!" cried he, holding out his hand to me. He invited me to dine with him on the following day, and we parted. I took care not to fail in my appointment. The conversation turned on the French Revolution, and the general showed us a key of the Bastille. Such was my meeting with the citizen soldier, the liberator of a world.

III. PARIS IN THE REIGN OF TERROR

In 1792, when I returned to Paris, it no longer exhibited the same appearance as in 1789 and 1790. It was no longer the new-born Revolution, but a people intoxicated, rushing on to fulfill its destiny across abysses and by devious ways. The appearance of the people was no longer curious and eager, but threatening.

The king's flight on June 21, 1791, gave an immense impulse to the Revolution. Having been brought back to Paris on June 25, he was dethroned for the first time, in consequence of the declaration of the National Assembly that all its decrees should have the force of law, without the king's concurrence or assent. I visited several of the "Clubs."

The scenes at the Cordeliers, at which I was three or four times present, were ruled and presided over by Danton, a Hun, with the nature of a Goth.

Faithful to my instincts, I had returned from America to offer my sword to Louis XVI., not to involve myself in party intrigues. I therefore decided to "emigrate." Brussels was the headquarters of the most distinguished émigrés. There I found my trifling baggage, which had arrived before me. The coxcomb émigrés were hateful to me. I was eager to see those like myself, with 600 livres income.

My brother remained at Brussels as an aide-de-camp to the Baron de Montboissier. I set out alone for Coblentz, went up the Rhine to that city, but the royal army was not there. Passing on, I fell in with the Prussian army between Coblentz and Treves. My white uniform caught the king's eye. He sent for me; he and the Duke of Brunswick took off their hats, and in my person saluted the old French army.

IV.- THE ARMY OF PRINCES

I was almost refused admission into the army of princes, for there were already too many gallant men ready to fight. But I said I had just come from America to have the honour of serving with old comrades. The matter was arranged, the ranks were opened to receive me, and the only remaining difficulty was where to choose. I entered the 7th company of the Bretons. We had tents, but were in want of everything else.

Our little army marched for Thionville. We went five or six leagues a day. The weather was desperate. We began the siege of Thionville, and in a few days were reinforced by Austrian cannon and cannoneers. The besieged made an attack on us, and in this action we had several wounded and some killed. We relinquished the siege of Thionville and set out for Verdun, which had surrendered to the allies. The passage of Frederic William was attested on all sides by garlands and flowers. In the midst of these trophies of peace I observed the Prussian eagle displayed on the fortifications of Verdun. It was not to remain long; as for the flowers, they were destined to fade, like the innocent creatures who had gathered them. One of the most atrocious murders of the reign of terror was that of the young girls of Verdun.

"Fourteen young girls of Verdun, of rare beauty, and almost like young virgins dressed for a public fête, were," says Riouffe, "led in a body to the scaffold. I never saw among us any despair like that which this infamous act excited."

I had been wounded during the siege of Thionville, and was suffering badly. While I was asleep, a splinter from a shell struck me on the right thigh. Roused by the stroke, but not being sensible of the pain, I only saw that I was wounded by the appearance of the blood. I bound up my thigh with my handkerchief. At four in the morning we thought the town had surrendered, but the gates were not opened, and we were obliged to think of a retreat. We returned to our positions after a harassing march of three days. While these drops of blood were shed under the walls of Thionville, torrents were flowing in the prisons of Paris; my wife and sisters were in greater danger than myself.

At Verdun, fever after my wound undermined my strength, and smallpox attacked me. Yet I began a journey on foot of two hundred leagues, with only eighteen livres in my pocket. All for the glory of the monarchy! I intended to try to reach Ostend, there to embark for Jersey, and thence to join the royalists in Brittany. Breaking down on the road, I lay insensible for two hours, swooning away with a feeling of religion. The last noise I heard was the whistling of a bullfinch. Some drivers of the Prince de Ligne's waggons saw me, and in pity lifted me up and carried me to Namur. Others of the prince's people carried me to Brussels. Here I found my brother, who brought a surgeon and a doctor to attend to me. He told me of the events of August 10, of the massacres of September, and other political news of which I had not heard. He approved of my intention to go to Jersey, and lent me twenty-five louis d'or. We were looking on each other for the last time.

After reaching Jersey, I was four months dangerously ill in my uncle's house, where I was tenderly nursed. Recovering, I went in 1793 to England, landing as a poor émigré where now, in 1822, I write these memoirs, and enjoy the dignity of ambassador.

V. LETTERS FROM THE DEAD

Several of my family fell victims to the Revolution. I learned in July, 1783, that my mother, after having been thrown, at the age of seventy-two, into a dungeon, where she witnessed the death of some of her children, expired at length on a pallet, to which her misfortunes had consigned her. The thoughts of my errors greatly embittered her last days, and on her death-bed she charged one of my sisters to reclaim me to the religion in which I had been educated. My sister Julie communicated my mother's last wish to me. When this letter reached me in my exile, my sister herself was no more; she, too, had sunk beneath the effects of her imprisonment. These two voices, coming as it were from the grave, the dead interpreting the dead had a powerful effect on me. I became a Christian. I did not, indeed, yield to any great supernatural light; my conviction came from my heart; I wept, I believed.

François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand (1768–1848) was a French writer, politician, diplomat and historian who founded Romanticism in French literature. Descended from an old aristocratic family from Brittany, Chateaubriand was a royalist by political disposition. In an age when a number of intellectuals turned against the Church, he authored the Génie du christianisme in defense of the Catholic faith. His works include the autobiography Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe ("Memoirs from Beyond the Grave"), published posthumously in 1849–1850.

Historian Peter Gay says that Chateaubriand saw himself as the greatest lover, the greatest writer, and the greatest philosopher of his age. Gay states that Chateaubriand "dominated the literary scene in France in the first half of the nineteenth century"

Labels:

PROSE,

QUOTES,

UNIVERSAL LITERATURE

Thursday, May 14, 2020

QUOTES ABOUT PANCAKES (+images)

Watching a woman make Russian pancakes, you might think that she was calling on the spirits or extracting from the batter the philosopher's stone. - Anton Chekhov

I thought English is a strange language. Now I think French is even more strange. In France, their fish is poisson, their bread is pain, and their pancake is crepe. Pain and poison and crap. That's what they have every day. - Xiaolu Guo

The laziest man I ever met put popcorn in his pancakes so they would turn over by themselves. - W. C. Fields

It was like the way you wanted sunshine on Saturdays, or pancakes for breakfast. They just made you feel good. - Sarah Addison Allen

I don't have to tell you I love you. I fed you pancakes. - Kathleen Flinn

For Sunday breakfast, I make orange and ricotta pancakes, crepes and eggs. You know men, we usually go for breakfast because it's the easiest thing to cook and then we try to make it seem fancy. - Hugh Jackman

I have people in my life, of course. Some write; some don't. Some read; some don't. Some stare vacantly into space when I talk the geeky talk and walk the geeky walk, but they make killer chocolate chip pancakes and so all is forgiven. - Rob Thurman

I can still memory - taste the fresh buttermilk pancakes and hot buttermilk biscuits - both made with lard! - that were cooked on the top, or in the oven, of that ancient iron stove. - Vernon L. Smith

I don't know what it is about food your mother makes for you, especially when it's something that anyone can make - pancakes, meat loaf, tuna salad - but it carries a certain taste of memory. - Mitch Albom

Someone who eats pancakes and jam can't be so awfully dangerous. You can talk to him. - Tove Jansson

We eat pancakes to escape loneliness, yet within moments we want nothing more than our freedom from ever having so much as thought about pancakes. Nothing can prevent us, after eating pancakes, from feeling the most awful regret. After eating pancakes, our great mission in life becomes the repudiation of the pancakes and everything served along with them, the bacon and the syrup and the sausage and coffee and jellies and jams. But these things are beneath mention, compared with the pancakes themselves. It is the pancake - Pancakes! Pancakes ! - that we never learn to respect. - Donald Antrim

I love adventurous travel. I also love pancakes, and making pancakes for other people. You would definitely find me in the airy treetop as opposed to below ground. - Kate DiCamillo

I love pancakes, and I actually do love healthy stuff. Like, I love gluten-free or whole-wheat pancakes. Breakfast is my favorite meal. - Ashley Tisdale

I used to work at The International House of Pancakes. It was a dream, and I made it happen. - Paula Poundstone

I order various types of breakfast and lunches. I do not just come in and order hamburgers all the time. I order the specials, pancakes, bacon and eggs. - John Brady

I'm like the queen of planning and scheduling and I'm trying very hard to stop it. I just want to finish what I'm doing and go home. I want to have a weekend. I want to have breakfast, a stack of pancakes. - Sandra Bullock

Where there is a perfect pancake flip, there is life. - Mahoatmeal Ghandi

There was no time for chit-chat when there were chocolate chip pancakes to be eaten - Kristen Day

Wednesday, March 11, 2020

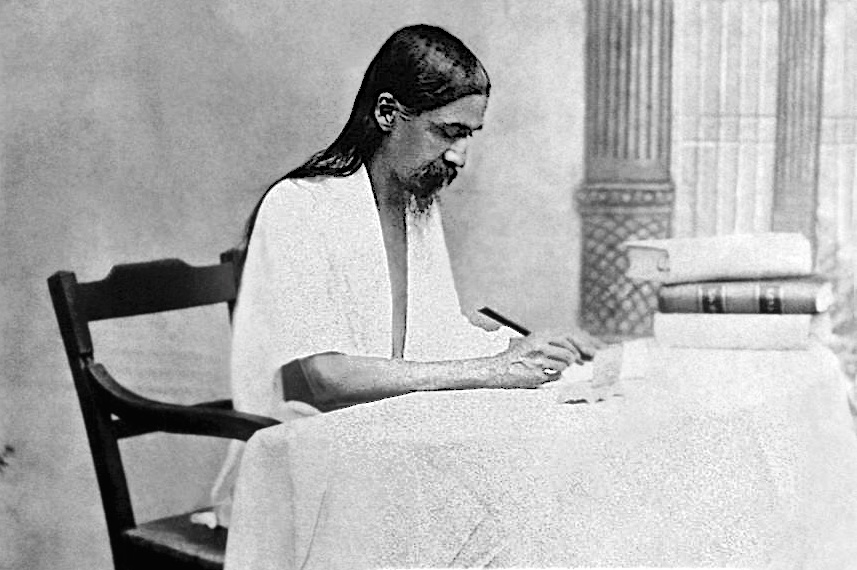

SRI AUROBINDO - Quotes from Savitri

Sri Aurobindo (born Aurobindo Ghose; 1872 – 1950) was an Indian philosopher, yogi, guru, poet, and nationalist.

All can be done

if the God-touch is there

Only a little

The God-light can stay.

A traveller between summit and abyss.

The human in him

Paced with the Divine.

God shall grow up

While the wise men

Talk and sleep.

We are sons of God

And must be even as he.

Beyond earth’s longitudes and latitudes.

Our life

Is a holocaust

Of the Supreme.

Oh, surely one day

He shall come to our cry.

None can reach heaven

Who has not

Passed through hell.

Our human state

Cradles the future god.

The One by whom all live,

Who lives by none.

Escape brings not the victory and the crown.

In absolute silence

Sleeps an absolute Power.

A God comes down greater by the fall.

A giant dance of Shiva tore the past.

Whoever is too great

Must lonely live.

The soul in man

Is greater

Than his fate.

The life you lead

Conceals the light you are.

The great are strongest

When they stand alone.

The day-bringer

Must walk

In darkest night.

Our life is a march

To a victory

Never won.

Man can accept his fate,

He can refuse.

His failure is not failure

Whom God leads.

One man’s perfection

Still can save the world.

He who would save the world

Must share its pain.

All is too little that the world can give.

I shall save earth,

If earth consents

To be saved.

He Who Chooses The Infinite Has Been Chosen by the Infinite

Truth born too soon

Might break

The imperfect earth.

A cave of darkness guards the eternal Light.

A death-bound littleness is not all we are.

A Light there is that leads,

A Power that aids.

A moment sees,

The ages toil to express.

All our earth starts from mud and ends in sky.

All rose from the silence;

All goes back to its hush.

All things are real

That here are only dreams.

An idiot hour destroys what centuries made.

Love is a yearning

Of the One

For the One.

Mortality bears ill

The eternal’s touch.

The spirit rises mightier

By defeat.

The soul that can

Live alone with itself

Meets God.

There is a purpose

In each stumble and fall.

A future knowledge is an added pain.

To know is best,

However hard to bear.

But few are they who tread the sunlit path.

Death helps us not,

Vain is the hope to cease.

Earth is the chosen place of mightiest souls.

Eternity speaks, none understands its word.

Fate shall be changed by an unchanging will.

For joy

And not for sorrow

Earth was made.

Heaven’s call is rare,

Rarer the heart that heeds.

My God is Love

And sweetly suffers all.

Only the pure in soul

Can walk in light.

The gods are still too few

In mortal forms.

We are greater

Than our thoughts.

Even the body shall remember God.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)