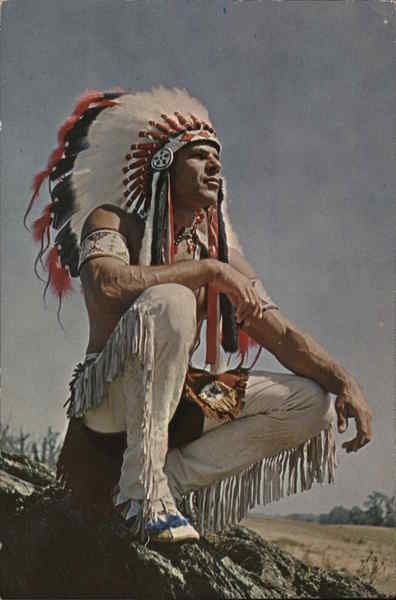

The Cree were plains

Indians. Today their village was full of activity. A hunting party had

just returned after a very successful hunt. The braves were already

around the great council fire, telling of their exploits. Among these

warriors was Slow Tongue, whose bravery and courage among the Cree was

never questioned.

When all the

celebrating was over, Slow Tongue returned to his tepee and his family.

His young son, Swift Hawk, had waited up for him and, with pride in his

eyes, he looked up into his father’s face and said, “I am very proud to

have you for my father.”

“My young son, it is

long past your bedtime and you should have closed your ears to the

night noises of the prairie many hours ago. But I must also say that I

am proud to have you as a son and tomorrow we shall talk and I shall

tell you all about the hunt. ” Slow Tongue turned to leave his son’s

side when he heard a noise at the entrance of his tepee.

“Slow Tongue,” a voice called quietly, “it is I, Seeing Bear. Come, I must speak with you. ”

Slow Tongue left the

tepee. “Why do you call me from my tepee so late in the night, Sleeping

Bear,” he asked. “I am tired and my buffalo robe beckons to me to come

and wrap myself in its warm folds, for my body aches.”

“Look, Slow Tongue!

Look to the north! At first I thought the heat of the day had made me

see things that do not exist. But now I am sure it has not. Look and

tell me what you see.”

Slow Tongue turned

his head to the north and gazed out into the darkness of the night. Far

in the distance he saw a red glow which disappeared, appeared again, and

disappeared many times.

“What can it mean, Slow Tongue?”

“It is a message,

Seeing Bear. The fire signal tells that the tribes of the plains are

gathering for the Sun Dance. Truly this is great news. Tomorrow we must

break camp and leave for the northern meadow of the Blue Star, for it is

there that the great celebrations will be held. You go to the southern

part of the village and I will go to the northern part, and we will

spread the word. It is late and many are asleep, but surely this is news

for which they will be glad to be awakened.”

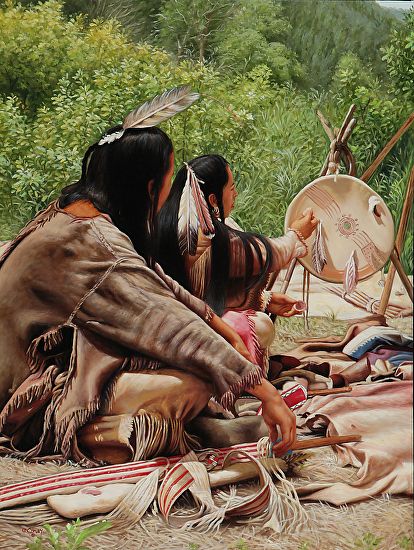

The next morning

there was great excitement in the Cree village. The gathering for the

Sun Dance not only meant gathering to celebrate the greatest religious

ceremony of the plains Indians, but it also meant that it would be a

time for great feasts, mock battles, ceremonial hunts, and the

recounting of the past year’s experience with many old friends. And, of

course, the men looked forward to smoking the ceremonial pipes which was

also a part of this great occasion.

The tribe had soon broken down its village and packed and the great procession headed north toward the meadow of the Blue Star.

For two days and two

nights the Cree village moved northward. Their progress was slow but

steady, and there was much gaiety. There was much to look forward to,

and many of the younger braves could hardly be kept from rushing on

ahead of the tribe.

Soon other tribes

began to join the Cree in their trek north. In all directions smoke

signals could be seen, sent up by eager messengers reporting the

movements of the tribes as they converged on the sacred grounds.

It was very clear to

Swift Hawk now that friend and enemy were walking side by side. This

was one time during the year when the burning desire to strike out at

your enemy was replaced by a stronger desire to do worship together in

the hope of a good year to come.

Soon the meadow of

the Blue Star was reached, and the tribe of Swift Hawk chose a place to

set its village in the great circle with the tribe’s sacred tepee as its

center. Campfires began to burn merrily, and the smell of cooking food

filled the air. Old and young warriors walked about to renew old

acquaintances and talk about what had happened during the past year.

Dancers could be seen here and there practicing seriously for the time

of the great ceremony.

Soon word spread

through the encampment that there were to be riding contests at the far

west side of the meadow on the following day. These contests would be

open to young braves who had made their first buffalo kill during the

last year. This made Swift Hawk leap and shout for joy. Just last month

he had brought down his first buffalo. This meant he could enter the

riding contest. For many years now Swift Hawk had watched the contests

from afar. Each year he promised himself that next year he would enter

and win. Each year his father told him to be patient and that his time

would come.

It was a very

difficult contest to test the skills of the young warriors. Each boy was

to start his ride from the top of a hill that sloped sharply down into

the meadow. At every one-hundred-yard point along a twisting path down

the steep slope, for a distance of five hundred yards, were four sets of

poles, two poles to each set. Each set was driven in the ground a

buffalo’s length apart until they stood between four and five feet above

ground. Between these two poles a buffalo hide was stretched to look

like a buffalo running directly toward the sloping path, his flank

toward the young warriors as they rode down.

Each young brave was

allowed a bow of his choice, four arrows, and a quiver. The brave, when

given the signal to go, would race down the slope at full speed.

Drawing an arrow from the quiver and bending his body down under the

neck of his pony and holding on with his feet, he would aim his arrow

under the neck of the pony and shoot the arrow into the buffalo hide. He

would do this with each of the four arrows.

Such a contest would

surely test the strength and courage of any young brave. But young

Indians were brought up to fear little and to welcome a test like this.

For this reason it was no surprise to the great chieftains when a rather

large group of young braves gathered at the starting point the next

morning. Each boy sat astride a fine looking pony, usually the gift of

his father or some other leading member of the tribe. Each boy had his

bow, his quiver, and four very special arrows which had been worked over

and cared for like a pet or one of the family.

Final instructions

were given to the young braves, and the riding contest was on! There was

a great cheer from all who were watching as each rider left the

starting point. This was a friendly match among boys from many tribes

that often fought each other the rest of the year. Down the steep slope a

lone warrior could be seen stationed at each buffalo hide. Here he

could not only retrieve arrows but help to judge the young braves as

they rode by and fired at the target.

Soon it was Swift

Hawk’s turn. Remembering all that his father had taught him, he dug his

heels into his pony’s sides and started his fast and dangerous ride.

Carefully he drew an arrow from the quiver; then bending under the

pony’s neck, he placed the arrow to the bow, and as the target came into

view, Swift Hawk let his arrow fly! He heard the plunk as the arrow

struck the hide. With his head still under the pony’s neck and riding so

hard, he could hardly have seen where it had landed. But a loud cheer

told him that he had made a good shot. Down the steep, winding course,

Swift Hawk swiftly shot his arrows at the three other targets, and went

back toward the starting point.

As he reached the

hilltop he heard a great shout go up. Looking down the course he saw a

young Crow brave just turning his pony to return to the starting point.

The loud cheer meant that he had ridden well and made many good hits.

One by one each of

the other young braves made his attempt but none could equal the riding

and skill of the young Crow Indian. And so it was when the last

contestant had made his ride and fired no better than the rest that the

Crow brave was announced as the winner. Swift Hawk was one of the first

to reach his side and congratulate him on his victory. Deep in his

heart, Swift Hawk was sad. But he was also very happy for this young

brave. Surely the young man had deserved to win; and, above all, Swift

Hawk realized how happy the young brave and his family must be that he

had won.

The contest over,

Swift Hawk returned to his home and his father, disappointed but not

unhappy now. There would be other contests, and this was a time of

celebration and joy. His father found him sitting beside a tree stump.

“You did very well,

my son,” Slow Tongue said, placing his hands upon Swift Hawk’s

shoulders. “The Crow boy who won did just a little bit better, but all

the Cree are proud of you. There will be other contests and many games.

Soon your turn will come. But even if it should not, remember what I

have told you. As long as you play fair with your fellow braves and obey

the rules, there is nothing to be ashamed of when you lose to someone

who plays fair and has great skill.”

“Thank you, father, I shall always remember that.”

Games and new

contests were beginning. Just as Swift Hawk’s father had told him, his

time would come and sooner than he expected. In the foot race he ran

much faster than any of his fellow braves, winning easily. Swift Hawk

was as good a winner as he had been a good loser, boasting to no one

about his victory.