ABOUT FACES

Watch the faces as

you walk along the street ! If you get the habit of noticing, your

observations will grow keener. It is surprising to see how seldom we

find a really quiet face. I do not mean that there should be no lines in

the face. We are here in this world at school and we cannot have any

real schooling unless we have real experiences. We cannot have real

experiences without suffering, and suffering which comes from the

discipline of life and results in character leaves lines in our faces.

It is the lines made by unnecessary strain to which I refer.

Strange to say the

unquiet faces come mostly from shallow feeling. Usually the deeper the

feeling the less strain there is on the face. A face may look troubled,

it may be full of pain, without a touch of that strain which comes from

shallow worry or excitement.

The strained

expression takes character out of the face, it weakens it, and certainly

it detracts greatly from whatever natural beauty there may have been to

begin with. The expression which comes from pain or any suffering well

borne gives character to the face and adds to its real beauty as well as

its strength.

To remove the

strained expression we must remove the strain behind; therefore the

hardest work we have to do is below the surface. The surface work is

comparatively easy.

I know a woman whose

face is quiet and placid. The lines are really beautiful, but they are

always the same. This woman used to watch herself in the glass until she

had her face as quiet and free from lines as she could get it, she used

even to arrange the corners of her mouth with her fingers until they

had just the right droop.

Then she observed

carefully how her face felt with that placid expression and studied to

keep it always with that feeling, until by and by her features were

fixed and now the placid face is always there, for she has established

in her brain an automatic vigilance over it that will not allow the

muscles once to get "out of drawing."

What kind of an old

woman this acquaintance of mine will make I do not know. I am curious to

see her, but now she certainly is a most remarkable hypocrite. The

strain in behind the mask of a face which she has made for herself must

be something frightful. And indeed I believe it is, for she is ill most

of the time and what could keep one in nervous illness more entirely

than this deep interior strain which is necessary to such external

appearance of placidity.

There comes to my

mind at once a very comical illustration of something quite akin to this

although at first thought it seems almost the reverse. A woman who

constantly talked of the preeminency of mind over matter, and the

impossibility of being moved by external circumstances to any one who

believed as she did, this woman I saw very angry.

She was sitting with

her face drawn in a hundred cross lines and all askew with her anger.

She had been spouting and sputtering what she called her righteous

indignation for some minutes, when after a brief pause and with the

angry expression still on her face she exclaimed: "Well, I don't care,

it's all peace within."

I doubt if my masked

lady would ever have declared to herself or to any one else that "it

was all peace within." The angry woman was - without doubt - the deeper

hypocrite, but the masked woman had become rigid in her hypocrisy. I do

not know which was the weaker of the two, probably the one who was

deceiving herself.

But to return to

those drawn, strained lines we see on the people about us. They do not

come from hard work or deep thought. They come from unnecessary

contractions about the work. If we use our wills consistently and

steadily to drop such contractions, the result is a more quiet and

restful way of living, and so quieter and more attractive faces.

This unquietness

comes especially in the eyes. It is a rare thing to see a really quiet

eye; and very pleasant and beautiful it is when we do see it. And the

more we see and observe the unquiet eyes and the unquiet faces the

better worth while it seems to work to have ours more quiet, but not to

put on a mask, or be in any other way a hypocrite.

The exercise

described in a previous chapter will help to bring a quiet face. We must

drop our heads with a sense of letting every strain go out of our

faces, and then let our heads carry our bodies down as far as possible,

dropping strain all the time, and while rising slowly we must take the

same care to drop all strain.

In taking the long

breath, we must inhale without effort, and exhale so easily that it

seems as if the breath went out of itself, like the balloons that

children blow up and then watch them shrink as the air leaves them.

Five minutes a day

is very little time to spend to get a quiet face, but just that five

minutes, if followed consistently will make us so much more sensitive to

the unquiet that we will sooner or later turn away from it as by a

natural instinct.

ABOUT VOICES

I Knew an old

German, a wonderful teacher of the speaking voice who said "the ancients

believed that the soul of the man is here" - pointing to the pit of his

stomach. "I do not know," and he shrugged his shoulders with expressive

interest, "it may be and it may not be, but I know the soul of the

voice is here, and you Americans, you squeeze the life out of the word

in your throat and it is born dead."

That old artist

spoke the truth, we Americans, most of us - do squeeze the life out of

our words and they are born dead. We squeeze the life out by the strain

which runs all through us and reflects itself especially in our voices.

Our throats are tense and closed; our stomachs are tense and strained;

with many of us the word is dead before it is born.

Watch people talking

in a very noisy place; hear how they scream at the top of their lungs

to get above the noise. Think of the amount of nervous force they use in

their efforts to be heard.

Now really when we

are in the midst of a great noise and want to be heard, what we have to

do is to pitch our voices on a different key from the noise about us. We

can be heard as well, and better, if we pitch our voices on a lower key

than if we pitch them on a higher key; and to pitch your voice on a low

key requires very much less effort than to strain to a high one.

I can imagine

talking with some one for half an hour in a noisy factory, for instance,

and being more rested at the end of the half hour than at the

beginning. Because to pitch your voice low you must drop some

superfluous tension and dropping superfluous tension is always restful.

I beg any or all of

my readers to try this experiment the next time they have to talk with a

friend in a noisy street. At first the habit of screaming above the

noise of the wheels is strong on us and it seems impossible that we

should be heard if we speak below it. It is difficult to pitch our

voices low and keep them there. But if we persist until we have formed a

new habit, the change is delightful.

There is one other

difficulty in the way; whoever is listening to us may be in the habit of

hearing a voice at high tension and so find it difficult at first to

adjust his ear to the lower voice and will in consequence insist that

the lower tone cannot be heard as easily.

It seems curious

that our ears can be so much engaged in expecting screaming that they

cannot without a positive effort of the mind readjust in order to listen

to a lower tone. But it is so. And, therefore, we must remember that to

be thoroughly successful in speaking intelligently below the noise we

must beg our listeners to change the habit of their ears as we ourselves

must change the pitch of our voices.

The result both to speaker and listener is worth the effort ten times over.

As we habitually

lower the pitch of our voices our words cease gradually to be "born

dead." With a low-pitched voice everything pertaining to the voice is

more open and flexible and can react more immediately to whatever may be

in our minds to express.

Moreover, the voice

itself may react back again upon our dispositions. If a woman gets

excited in an argument, especially if she loses her temper, her voice

will be raised higher and higher until it reaches almost a shriek. And

to hear two women "argue" sometimes it may be truly said that we are

listening to a "caterwauling." That is the only word that will describe

it.

But if one of these

women is sensitive enough to know she is beginning to strain in her

argument and will lower her voice and persist in keeping it lowered the

effect upon herself and the other woman will put the "caterwauling" out

of the question.

"Caterwauling" is an

ugly word. It describes an ugly sound. If you have ever found yourself

in the past aiding and abetting such an ugly sound in argument with

another say to yourself "caterwauling," "caterwauling," "I have been

'caterwauling' with Jane Smith, or Maria Jones," or whoever it may be,

and that will bring out in such clear relief the ugliness of the word

and the sound that you will turn earnestly toward a more quiet way of

speaking.

The next time you

start on the strain of an argument and your voice begins to go up, up,

up - something will whisper in your ear "caterwauling" and you will at

once, in self-defense, lower your voice or stop speaking altogether.

It is good to call

ugly things by their ugliest names. It helps us to see them in their

true light and makes us more earnest in our efforts to get away from

them altogether.

I was once a guest

at a large reception and the noise of talking seemed to be a roar, when

suddenly an elderly man got up on a chair and called "silence," and

having obtained silence he said, "it has been suggested that every one

in this room should speak in a lower tone of voice."

The response was

immediate. Every one went on talking with the same interest only in a

lower tone of voice with a result that was both delightful and soothing.

I say every one,

there were perhaps half a dozen whom I observed who looked and I have no

doubt said "how impudent." So it was "impudent" if you chose to take it

so, but most of the people did not choose to take it so and so brought a

more quiet atmosphere and a happy change of tone.

Theophile Gautier

said that the voice was nearer the soul than any other expressive part

of us. It is certainly a very striking indicator of the state of the

soul. If we accustom ourselves to listen to the voices of those about us

we detect more and more clearly various qualities of the man or the

woman in the voice, and if we grow sensitive to the strain in our own

voices and drop it at once when it is perceived, we feel a proportionate

gain.

I knew of a blind

doctor who habitually told character by the tone of the voice, and men

and women often went to him to have their characters described as one

would go to a palmist.

Once a woman spoke

to him earnestly for that purpose and he replied, "Madam, your voice has

been so much cultivated that there is nothing of you in it - I cannot

tell your real character at all." The only way to cultivate a voice is

to open it to its best possibilities, not to teach its owner to pose or

to imitate a beautiful tone until it has acquired the beautiful tone

habit. Such tones are always artificial and the unreality in them can be

easily detected by a quick ear.

Most great singers

are arrant hypocrites. There is nothing of themselves in their tone. The

trouble is to have a really beautiful voice one must have a really

beautiful soul behind it.

If you drop the

tension of your voice in an argument for the sake of getting a clearer

mind and meeting your opponent without resistance, your voice helps your

mind and your mind helps your voice.

They act and react

upon one another with mutual benefit. If you lower your voice in general

for the sake of being more quiet, and so more agreeable and useful to

those about you, then again the mental or moral effort and the physical

effort help one another.

It adds greatly to a

woman's attraction and to her use to have a low, quiet voice and if any

reader is persisting in the effort to get five minutes absolute quiet

in every day let her finish the exercise by saying something in a quiet,

restful tone of voice.

It will make her more sensitive to her unrestful tones outside, and so help her to improve them.

ABOUT FRIGHTS

Here are two true

stories and a remarkable contrast. A nerve specialist was called to see a

young girl who had had nervous prostration for two years. The physician

was told before seeing the patient that the illness had started through

fright occasioned by the patient's waking and discovering a burglar in

her room.

Almost the moment

the doctor entered the sick room, he was accosted with: "Doctor, do you

know what made me ill ? It was frightful." Then followed a minute

description of her sudden awakening and seeing the man at her bureau

drawers.

This story had been

lived over and over by the young girl and her friends for two years,

until the strain in her brain caused by the repetition of the impression

of fright was so intense that no skill nor tact seemed able to remove

it. She simply would not let it go, and she never got really well.

Now, see the

contrast. Another young woman had a similar burglar experience, and for

several nights after she woke with a start at the same hour. For the

first two or three nights she lay and shivered until she shivered

herself to sleep.

Then she noticed how

tightened up she was in every muscle when she woke, and she bethought

herself that she would put her mind on relaxing her muscles and getting

rid of the tension in her nerves. She did this persistently, so that

when she woke with the burglar fright it was at once a reminder to

relax.

After a little she

got the impression that she woke in order to relax and it was only a

very little while before she succeeded so well that she did not wake

until it was time to get up in the morning.

The burglar

impression not only left her entirely, but left her with the habit of

dropping all contractions before she went to sleep, and her nerves are

stronger and more normal in consequence.

The

two girls had each a very sensitive, nervous temperament, and the

contrast in their behavior was simply a matter of intelligence.

This same

nerve specialist received a patient once who was positively blatant in

her complaint of a nervous shock. "Doctor, I have had a horrible nervous

shock. It was horrible. I do not see how I can ever get over it."

Then she

told it and brought the horrors out in weird, over-vivid colors. It was

horrible, but she was increasing the horrors by the way in which she

dwelt on it.

Finally,

when she paused long enough to give the doctor an opportunity to speak,

he said, very quietly: "Madam, will you kindly say to me, as gently as

you can, 'I have had a severe nervous shock." She looked at him without a

gleam of understanding and repeated the words quietly: "I have had a

severe nervous shock."

In spite of

herself she felt the contrast in her own brain. The habitual blatancy

was slightly checked. The doctor then tried to impress upon her the fact

that she was constantly increasing the strain of the shock by the way

she spoke of it and the way she thought of it, and that she was really

keeping herself ill.

Gradually,

as she learned to relax the nervous tension caused by the shock, a true

intelligence about it all dawned upon her; the over-vivid colors faded,

and she got well. She was surprised herself at the rapidity with which

she got well, but she seemed to understand the process and to be

moderately grateful for it.

If she had

had a more sensitive temperament she would have appreciated it all the

more keenly; but if she had had a more sensitive temperament she would

not have been blatant about her shock.

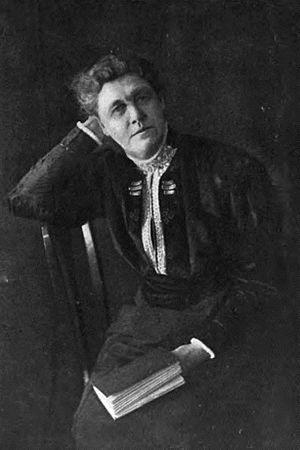

Annie Payson Call (1853–1940) was a Waltham author.

She wrote several books and published articles in "Ladies' Home Journal".

Many articles are reprinted in her book "Nerves and Common Sense".

The common theme of her work is mental health.