"I must send for Jules," he kept muttering; "Jules knew her well; he was one of her oldest friends; he would help me in a case like this, I feel sure. He always told her that green diamonds were unlucky; I was insane to touch the things, positively insane. Jules will come at once, and I will tell him everything, and he will explain things we do not understand. Perhaps you will send a letter to him now; Robert is in the kitchen and he will take it."

"I will send a note with pleasure if you think this man can help us; but who is he, and why have I not heard of him before?"

"You must have heard of him," he answered testily; "he was always with us when she lived—always."

"Do you see him often now?"

"Yes, often; he was here a week ago; that is his photograph on the cabinet there."

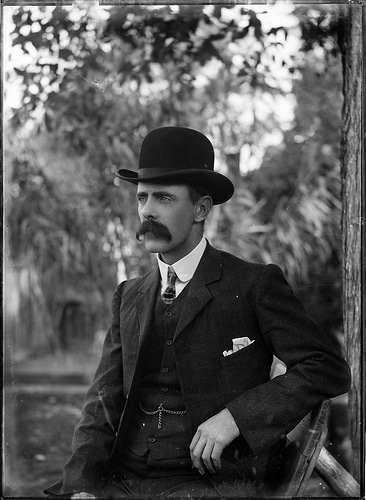

The picture was that of a finely built but very typical Frenchman, a man with a pointed, well-brushed beard, and a neatly curled mustache. The head was not striking, being cramped above the eyes and bulging behind the ears; but the smile was very pleasant, and the general effect one of geniality. I examined the photograph, and then asked casually:

"What is this M. Jules? you don't tell me the rest of his name."

"Jules Galimard. I must have mentioned him to you. He is the editor, or something, of Paris et Londres. We will write for him now, and he will come over at once."

I sent the letter to please him, asking the man to come across on important business, and then told him of my plan.

"The first thing to do," said I, "is to go to Raincy, and to ascertain if the grave of your wife has been tampered with—and when. If you will stay here and nurse yourself, I will do that at once?"

He seemed to think over the proposition for some minutes; and when he answered me he was calmer.

"I will come with you," he said; "if—if any one is to look upon her face again, it shall be me."

I could see that a terrible love gave him strength even for such an ordeal as this. He began to be meaningly and even alarmingly calm; and when we set out for Raincy he betrayed no emotion whatever. I will not describe anything but the result of that never-to-be-forgotten mission, although the scene haunts my memory to this day. Suffice it to say that we found indisputable evidence of a raid upon the vault; and discovered that the necklace had been torn from the body of the woman. When nothing more was to be learnt, I took my friend back to Paris. There I found a letter from the office of Paris et Londres saying that Galimard was at Dieppe but would be with us in the evening.

The mystery had now taken such hold of me that I could not rest. Brewer, whose calm was rather dangerous than reassuring, seemed strangely lethargic when he reached his rooms, and began to doze in his arm-chair. This was the best thing he could have done; but I had no intention of dozing myself; and when I had wormed from him the address of the shop where the sham necklace had been purchased—it proved to be in the Rue Stockholm—I took a fiacre at once and left him to his dreaming. The place was a poor one, though the taste of a Frenchman was apparent in the display and arrangement of the few jewels, bronzes, and pictures which were the stock-in-trade of the dealer. He himself was a lifeless creature, who listened to me with great patience, and appeared to be completely astounded when I told him that I desired to have an interview with the vendor of the necklace and the green diamonds.

"You could not have come at a more fortunate moment," said he, "the stones were pretty, I confess and I fear to have sold them for much less than they were worth; but my client will be here in half an hour for his money, and if you come at that time you can meet him."

This was positive and altogether unlooked-for luck. I spent the thirty minutes' interval in a neighboring café, and was back at his shop as the clocks were striking seven. His customer was already there; a man short and thick in figure, with a characteristic French low hat stuck on the side of his head; and an old black cutaway coat which was conspicuously English. He wore gaiters, too—a strange sight in Paris; and carried under his arm a rattan cane which was quite ridiculously short. When he turned his head I saw that his hair was cropped quite close, and that he had a great scar down one side of his face, which gave him a hideous appearance. Yet he could not have been twenty-five years of age; and he was one of the gayest customers I have ever met.

"Oh," he said, looking me up and down critically, and with a perky cock of his head, "you're the cove that wants to speak to me about the sparklers, are you? and a damned well-dressed cove, too. I thought you were one of these French hogs."

"I wanted to have a chat about such wonderful imitations," I said, "and am English like yourself."

At this he raked up the gold which the old dealer had placed upon the counter for him and went to the door rapidly, where he stood with his hands upon his hips, and a wondrous knowing smile in his bit of an eye.

"You're a pretty nark, ain't you?" he said, "a fine slap-up Piccadilly thick-un, s' help me blazes; and you ain't got no bracelets in your pockets, and there ain't no more of you round the corner. Oh, hell! but this is funny!"

"I am quite alone," I said quickly, seeing that the game was nearly lost, "and if you tell me what I want to know, I will give you as much money as you have in your hand there, and you have my word that you shall go quite free."

"Your word!" he replied, looking more knowing than ever; "that's a ripping fine Bank of Engraving to go on bail on, ain't it? Who are you, and how's your family?"

"Let's stroll down the street, any way you like," said I, "and talk of it. Choose your own course, and then you will be sure that I am alone."

He looked at me for a minute, walking slowly. Then suddenly he stopped abruptly, and put his hand upon a pocket at his waist.

"Guv'ner," he said, "lay your fingers on that; do you feel it? it's a Colt, ain't it? Well, if you want to get me in on the bow, I tell you I'll go the whole hog, so you know."

"I assure you again that I have no intention of troubling you with anything but a few questions; and I give you my word that anything you tell me shall not be used against you afterwards. It's the other man we want to catch the man who took the green diamonds which were not shams."

This thought was quite an inspiration. He considered it for a moment, standing still under the lamp; but at last he stamped his foot and whistled, saying:

"You want him, do you? well, so do I; and if I could punch his head I'd walk a mile to do it. You come to my room, guv'ner, and I'll take my chance of the rest."

The way lay past the Chapel of the Trinity, and so through many narrow streets to one which seemed the center of a particularly dark and uninviting neighborhood. The man, who told me in quite an affable mood that his name was Bob Williams, and that he hoped to run against me at Auteuil, had a miserable apartment on the "third" of a house in this dingy street; and there he took me, offering me half-a-tumbler of neat whisky, which, he went on to explain, would "knock flies" out of me. For himself, he sat upon a low bed and smoked a clay pipe,[ 48] while I had an arm-chair, lacking springs; and one of my cigars for obvious reasons. When we were thus accommodated he opened the ball, being no longer nervous or hesitating.

"Well, old chap,"—I was that already to him—"what can I tell you, and what do you know?"

"I know this much," said I; "last month the grave of Madame Brewer at Raincy was rifled. The man who did it stole a necklace of green diamonds, real or sham, but the latter, I am thinking."

"As true as gospel—I was the man who took them, and they were sham, and be damned to them!"

"Well, you're a pretty ruffian," I said. "But what I want to know is, how did you come to find out that the stones were there, and who was the man who got the real necklace I made for Madame Brewer only a few months ago?"

"Oh, that's what you want to know, is it? Well, it's worth something, that is; I don't know that he ain't a pard of mine; and about no other necklace I ain't heard nothing. You know a blarmed sight too much, it seems to me, guv'ner."

"That may be," said I, "but you can add to what I know, and it might be worth fifty pounds to you."

"On the cushion?"

"I don't understand."

"Well, on that table then?"

"Scarcely. Twenty-five now, and twenty-five when I find that you have told me the truth."

"Let's see the shiners."

I counted out the money on to the bed—five English bank notes, which he eyed suspiciously.

"May, his mark," he said, thumbing the paper. "Well, as I'm shifting for Newmarket to-morrow that's not much odds, if you're not shoving the queer on me."

"Do you think they're bad?"

"I'll tell you in a moment; i broken, e broken, watermark right; guv'ner, I'll put up with 'em. Now, what do you want to know?"

"I want to know how you came to learn that the stones were in Madame Brewer's grave?"

"A straight question. Well, I was told by a pal."

"Is he here in Paris?"

"He ought to be; he told me his name was Mougat, but I found out that it ain't. He is a chap that writes for the papers and runs that rag with the rum pictures in it; what do you call it, Paris and something or other?"

"Paris et Londres," I ventured at hazard.

"Ay, that's the thing; I don't read much of the lingo myself, but I gave him tips at Longchamps last month, and we came back in a dog-cart together. It was then that he put me on to the stones and planted me with a false name."

"What did he say?"

"Said that some mad cove at Raincy had buried a necklace worth two thousand pounds with his wife, and that the dullest chap out could get into the vault and lift it. I'd had a bad day, and was almost stony. He kept harping on the thing so, suggesting that a man could get to America with five thousand in his pocket, and no one be a penny the wiser or a penny the worse, that I went off that night and did it, and got a fine heap for my pains. That's what I call a mouldy pal—a pal I wouldn't make a doormat of."

"And you sold the booty to the old Frenchman in the Rue de Stockholm?"

"Exactly! he gave me a tenner for it, and I'm crossing to England to-night. No place like the old shop, guv'ner, when the French hogs are sniffing about you. I guess there's a few of them will want me in Parry in a day or two; and that reminds me, you can do the noble if you like, and send the other chips to the Elephant Hotel at Cambridge last post to-morrow."

I told him that I would, and left. You may ask why I had any truck with such a complete blackguard, but the answer is obvious: I had guessed from the first that there was something in the mystery of the green diamonds which would not bear exposure from Brewer's point of view, and his tale confirmed the opinion. I had learnt from it two obvious facts: one that Jules Galimard was anything but the friend of my friend; the other, that this man knew perfectly well that a sham diamond necklace was buried with Madame Brewer. It came to me then, as in a flash, that he, and he alone, must have stolen, or at least have come into possession of, the real necklace which I had made.

How to undeceive the good soul who had entrusted me with his case was the remaining difficulty. He had loved this woman so; and yet instinct suggested to me that she had been unworthy of his deep affection. That she had been untrue to him I did not know. Galimard might have stolen the jewels from her, and have replaced them with a false set; on the other hand, she might have been a party to the fraud. What, then, should I say, or how much should I dare with the great responsibility before me of crushing a man whose heart was already broken?

With such thoughts I re-entered the apartment in the Rue de Morny. As I did so, the servant put a telegram into my hand, and told me that M. Jules Galimard was with his master. Fate, however, seemed to have given the man another chance, for the cipher said,—

"Green and Co. in error, they should have sent the stones only; necklace not for sale; client's name unknown, acting for Paris agents."

I walked into the room with this message in my pocket; and when Brewer saw me he jumped up with delight, and introduced me to a well-dressed Frenchman who had the red rosette in the buttonhole of his faultless frock-coat, and who showed a row of admirable teeth when he smiled to greet me.

"Here is Jules," said Brewer, "my friend I have spoken of, M. Jules Galimard; he has come to help us, as I said he would; there is no one whose advice I would sooner take in this horrible matter."

I bowed stiffly to the man, and seated myself on the opposite side of the table to him. As they seemed to wait for me to speak, I took up the question at once.

"Well," I said, speaking to Brewer; but turning round to look at his friend, as I uttered the words, "I have found out who sold the sham necklace to the man in the Rue de Stockholm; the rogue is a racing tout named Bob Williams!"

Galimard turned right round in his chair at this, and put his elbows on the table. Brewer said, "God bless me, what a scamp!"

"And," I continued, "the extraordinary part of the affair is that this scoundrel was put to the business by a man he met at Longchamps last month. It is obvious that this man stole the real necklace, and now desired all traces of his handiwork to be removed from Madame Brewer's coffin. I have his name," with which direct remark I looked hard at the fellow, and he rose straight up from his chair and clutched at the back of it with his hand. For a moment he seemed speechless; but when he found his tongue, he threw away, with dreadful maladroitness, the opening I had given him.

"Madame gave me the jewels," he blurted out, "that I will swear before any court."

The situation was truly terrible, the man standing gripping his chair, Brewer staring at both of us as at lunatics.

"What do you say? What's that?" he cried; and the assertion was repeated.

"I am no thief!" cried the man, drawing himself up in a way that was grotesquely proud, "she gave me the jewels, your wife, a week after you gave them to her. I had a false set made so that you should not miss them; here is her letter in which she acknowledges the receipt of them."

The old man—for he was an old man then in speech, in look, and in the fearful convulsions of his face—sprung from his chair, and struck the rascal who told him the tale full in the mouth with his clenched fist. The fellow rolled backwards, striking his head against the iron of the fender; and lay insensible for many minutes. During that time I called a cab, and when he was capable of being moved, sent him away in it. I saw clearly that for Brewer's sake the matter must be hushed at once, blocked out as a page in a life which had been false in its every line. Nor did I pay any attention to Galimard's raving threat that his friends should call upon me in half an hour; but went upstairs again to find the best soul that ever lived sitting over the fire which had been lighted for him, and chattering with the cackle of the insane. He had the letter, which Galimard had thrown down, in his hands, and he read it aloud with hysterical laughter and awful emphasis.

I tried to speak to him, to reason with him, to persuade him. He heard nothing I said, but continued to chuckle and to chatter in a way that made my blood run cold. Then suddenly he became very calm, sitting bolt upright in his chair, with the letter clutched tightly in his right hand; and I saw that tears were rolling down his cheeks.

An hour later the friends of M. Jules Galimard called. They entered the room noisily, but I hushed them, for the man was dead!