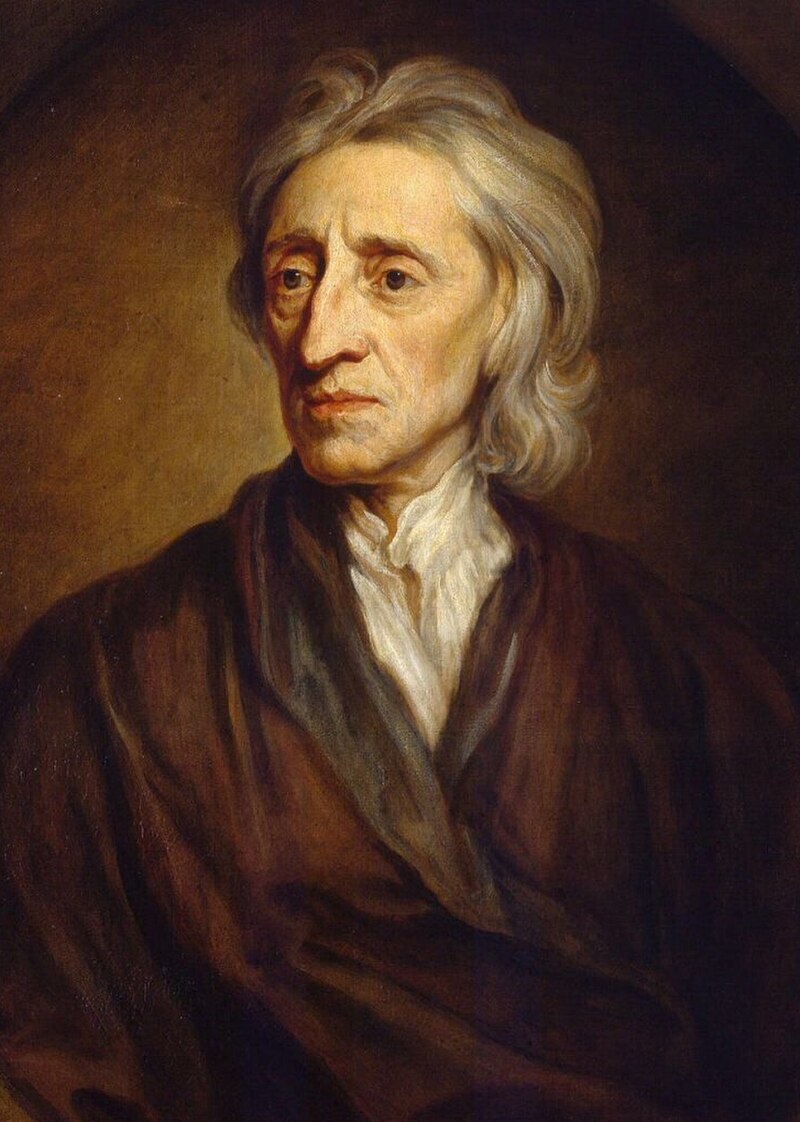

John Locke - 1632 – 1704

A good portrait of Locke would require an elaborate background. His is not a figure to stand statuesquely in a void: the pose might not seem grand enough for bronze or marble. Rather he should be painted in the manner of the Dutch masters, in a sunny interior, scrupulously furnished with all the implements of domestic comfort and philosophic enquiry: the Holy Bible open majestically before him, and beside it that other revelation - the terrestrial globe. His hand might be pointing to a microscope set for examining the internal constitution of a beetle: but for the moment his eye should be seen wandering through the open window, to admire the blessings of thrift and liberty manifest in the people so worthily busy in the market-place, wrong as many a monkish notion might be that still troubled their poor heads. From them his enlarged thoughts would easily pass to the stout carved ships in the river beyond, intrepidly setting sail for the Indies, or for savage America. Yes, he too had travelled, and not only in thought. He knew how many strange nations and false religions lodged in this round earth, itself but a speck in the universe. There were few ingenious authors that he had not perused, or philosophical instruments that he had not, as far as possible, examined and tested; and no man better than he could understand and prize the recent discoveries of "the incomparable Mr Newton". Nevertheless, a certain uneasiness in that spare frame, a certain knitting of the brows in that aquiline countenance, would suggest that in the midst of their earnest eloquence the philosopher's thoughts might sometimes come to a stand. Indeed, the visible scene did not exhaust the complexity of his problem; for there was also what he called "the scene of ideas", immaterial and private, but often more crowded and pressing than the public scene. Locke was the father of modern psychology, and the birth of this airy monster, this half-natural changeling, was not altogether easy or fortunate.

I wish my erudition allowed me to fill in this picture as the subject deserves, and to trace home the sources of Locke's opinions, and their immense influence. Unfortunately, I can consider him - what is hardly fair - only as a pure philosopher: for had Locke's mind been more profound, it might have been less influential. He was in sympathy with the coming age, and was able to guide it: an age that confided in easy, eloquent reasoning, and proposed to be saved, in this world and the next, with as little philosophy and as little religion as possible. Locke played in the eighteenth century very much the part that fell to Kant in the nineteenth. When quarrelled with, no less than when embraced, his opinions became a point of departure for universal developments. The more we look into the matter, the more we are impressed by the patriarchal dignity of Locke's mind. Father of psychology, father of the criticism of knowledge, father of theoretical liberalism, godfather at least of the American political system, of Voltaire and the Encyclopaedia, at home he was the ancestor of that whole school of polite moderate opinion which can unite liberal Christianity with mechanical science and with psychological idealism. He was invincibly rooted in a prudential morality, in a rationalised Protestantism, in respect for liberty and law: above all he was deeply convinced, as he puts it, "that the handsome conveniences of life are better than nasty penury". Locke still speaks, or spoke until lately, through many a modern mind, when this mind was most sincere; and two hundred years before Queen Victoria he was a Victorian in essence.

A chief element in this modernness of Locke was something that had hardly appeared before in pure philosophy, although common in religion: I mean, the tendency to deny one's own presuppositions - not by accident or inadvertently, but proudly and with an air of triumph. Presuppositions are imposed on all of us by life itself: for instance the presupposition that life is to continue, and that it is worth living. Belief is born on the wing and awakes to many tacit commitments. Afterwards, in reflection, we may wonder at finding these presuppositions on our hands and, being ignorant of the natural causes which have imposed them on the animal mind, we may be offended at them. Their arbitrary and dogmatic character will tempt us to condemn them, and to take for granted that the analysis which undermines them is justified, and will prove fruitful. But this critical assurance in its turn seems to rely on a dubious presupposition, namely, that human opinion must always evolve in a single line, dialectically, providentially, and irresistibly. It is at least conceivable that the opposite should sometimes be the case. Some of the primitive presuppositions of human reason might have been correct and inevitable, whilst the tendency to deny them might have sprung from a plausible misunderstanding, or the exaggeration of a half-truth: so that the critical opinion itself, after destroying the spontaneous assumptions on which it rested, might be incapable of subsisting.

In Locke the central presuppositions, which he embraced heartily and without question, were those of common sense. He adopted what he calls a "plain, historical method", fit, in his own words, "to be brought into well-bred company and polite conversation". Men, "barely by the use of their natural faculties", might attain to all the knowledge possible or worth having. All children, he writes, "that are born into this world, being surrounded with bodies that perpetually and diversely affect them" have "a variety of ideas imprinted" on their minds. "External material things as objects of Sensation, and the operations of our own minds as objects of Reflection, are to me", he continues, "the only originals from which all our ideas take their beginnings." "Every act of sensation", he writes elsewhere, "when duly considered, gives us an equal view of both parts of nature, the corporeal and the spiritual. For whilst I know, by seeing or hearing,... that there is some corporeal being without me, the object of that sensation, I do more certainly know that there is some spiritual being within me that sees and hears."

Resting on these clear perceptions, the natural philosophy of Locke falls into two parts, one strictly physical and scientific, the other critical and psychological. In respect to the composition of matter, Locke accepted the most advanced theory of his day, which happened to be a very old one: the theory of Democritus that the material universe contains nothing but a multitude of solid atoms coursing through infinite space: but Locke added a religious note to this materialism by suggesting that infinite space, in its sublimity, must be an attribute of God. He also believed what few materialists would venture to assert, that if we could thoroughly examine the cosmic mechanism we should see the demonstrable necessity of every complication that ensues, even of the existence and character of mind: for it was no harder for God to endow matter with the power of thinking than to endow it with the power of moving.

In the atomic theory we have a graphic image asserted to describe accurately, or even exhaustively, the intrinsic constitution of things, or their primary qualities. Perhaps, in so far as physical hypotheses must remain graphic at all, it is an inevitable theory. It was first suggested by the wearing out and dissolution of all material objects, and by the specks of dust floating in a sunbeam; and it is confirmed, on an enlarged scale, by the stellar universe as conceived by modern astronomy. When today we talk of nuclei and electrons, if we imagine them at all, we imagine them as atoms. But it is all a picture, prophesying what we might see through a sufficiently powerful microscope; the important philosophical question is the one raised by the other half of Locke's natural philosophy, by optics and the general criticism of perception. How far, if at all, may we trust the images in our minds to reveal the nature of external things?

On this point the doctrine of Locke, through Descartes, was also derived from Democritus. It was that all the sensible qualities of things, except position, shape, solidity, number and motion, were only ideas in us, projected and falsely regarded as lodged in things. In the things, these imputed or secondary qualities were simply powers, inherent in their atomic constitution, and calculated to excite sensations of that character in our bodies. This doctrine is readily established by Locke's plain historical method, when applied to the study of rainbows, mirrors, effects of perspective, dreams, jaundice, madness, and the will to believe: all of which go to convince us that the ideas which we impulsively assume to be qualities of objects are always, in their seat and origin, evolved in our own heads.

These two parts of Locke's natural philosophy, however, are not in perfect equilibrium. All the feelings and ideas of an animal must be equally conditioned by his organs and passions, and he cannot be aware of what goes on beyond him, except as it affects his own life. How then could Locke, or could Democritus, suppose that his ideas of space and atoms were less human, less graphic, summary, and symbolic, than his sensations of sound or colour? The language of science, no less than that of sense, should have been recognised to be a human language; and the nature of anything existent collateral with ourselves, be that collateral existence material or mental, should have been confessed to be a subject for faith and for hypothesis, never, by any possibility, for absolute or direct intuition.

There is no occasion to take alarm at this doctrine as if it condemned us to solitary confinement, and to ignorance of the world in which we live. We see and know the world through our eyes and our intelligence, in visual and in intellectual terms: how else should a world be seen or known which is not the figment of a dream, but a collateral power, pressing and alien? In the cognisance which an animal may take of his surroundings, and surely all animals take such cognisance, the subjective and moral character of his feelings, on finding himself so surrounded, does not destroy their cognitive value. These feelings, as Locke says, are signs: to take them for signs is the essence of intelligence. Animals that are sensitive physically are also sensitive morally, and feel the friendliness or hostility which surrounds them. Even pain and pleasure are no idle sensations, satisfied with their own presence: they violently summon attention to the objects that are their source. Can love or hate be felt without being felt towards something, something near and potent, yet external, uncontrolled, and mysterious? When I dodge a missile or pick a berry, is it likely that my mind should stop to dwell on its pure sensations or ideas without recognising or pursuing something material? Analytic reflection often ignores the essential energy of mind, which is originally more intelligent than sensuous, more appetitive and dogmatic than aesthetic. But the feelings and ideas of an active animal cannot help uniting internal moral intensity with external physical reference; and the natural conditions of sensibility require that perceptions should owe their existence and quality to the living organism with its moral bias, and that at the same time they should be addressed to the external objects which entice that organism or threaten it.

All ambitions must be defeated when they ask for the impossible. The ambition to know is not an exception; and certainly our perceptions cannot tell us how the world would look if nobody saw it, or how valuable it would be if nobody cared for it. But our perceptions, as Locke again said, are sufficient for our welfare and appropriate to our condition. They are not only a wonderful entertainment in themselves, but apart from their sensuous and grammatical quality, by their distribution and method of variation, they may inform us most exactly about the order and mechanism of nature. We see in the science of today how completely the most accurate knowledge, proved to be accurate by its application in the arts, may shed every pictorial element, and the whole language of experience, to become a pure method of calculation and control. And by a pleasant compensation, our aesthetic life may become freer, more self-sufficing, more humbly happy in itself: and without trespassing in any way beyond the modesty of nature, we may consent to be like little children, chirping our human note; since the life of reason in us may well become science in its validity, whilst remaining poetry in its texture.

I think, then, that by a slight re-arrangement of Locke's pronouncements in natural philosophy, they could be made inwardly consistent, and still faithful to the first presuppositions of common sense, although certainly far more chastened and sceptical than impulsive opinion is likely to be in the first instance.

There were other presuppositions in the philosophy of Locke besides his fundamental naturalism; and in his private mind probably the most important was his Christian faith, which was not only confident and sincere, but prompted him at times to high speculation. He had friends among the Cambridge Platonists, and he found in Newton a brilliant example of scientific rigour capped with mystical insights. Yet if we consider Locke's philosophical position in the abstract, his Christianity almost disappears. In form his theology and ethics were strictly rationalistic; yet one who was a Deist in philosophy might remain a Christian in religion. There was no great harm in a special revelation, provided it were simple and short, and left the broad field of truth open in almost every direction to free and personal investigation. A free man and a good man would certainly never admit, as coming from God, any doctrine contrary to his private reason or political interest; and the moral precepts actually vouchsafed to us in the Gospels were most acceptable, seeing that they added a sublime eloquence to maxims which sound reason would have arrived at in any case.

Evidently common sense had nothing to fear from religious faith of this character; but the matter could not end there. Common sense is not more convinced of anything than of the difference between good and evil, advantage and disaster; and it cannot dispense with a moral interpretation of the universe. Socrates, who spoke initially for common sense, even thought the moral interpretation of existence the whole of philosophy. He would not have seen anything comic in the satire of Molière making his chorus of young doctors chant in unison that opium causes sleep because it has a dormitive virtue. The virtues or moral uses of things, according to Socrates, were the reason why the things had been created and were what they were; the admirable virtues of opium defined its perfection, and the perfection of a thing was the full manifestation of its deepest nature. Doubtless this moral interpretation of the universe had been overdone, and it had been a capital error in Socrates to make that interpretation exclusive and to substitute it for natural philosophy. Locke, who was himself a medical man, knew what a black cloak for ignorance and villainy Scholastic verbiage might be in that profession. He also knew, being an enthusiast for experimental science, that in order to control the movement of matter, which is to realise those virtues and perfections, it is better to trace the movement of matter materialistically; for it is in the act of manifesting its own powers, and not, as Socrates and the Scholastics fancied, by obeying a foreign magic, that matter sometimes assumes or restores the forms so precious in the healer's or the moralist's eyes. At the same time, the manner in which the moral world rests upon the natural, though divined, perhaps, by a few philosophers, has not been generally understood; and Locke, whose broad humanity could not exclude the moral interpretation of nature, was driven in the end to the view of Socrates. He seriously invoked the Scholastic maxim that nothing can produce that which it does not contain. For this reason the unconscious, after all, could never have given rise to consciousness. Observation and experiment could not be allowed to decide this point: the moral interpretation of things, because more deeply rooted in human experience, must envelop the physical interpretation, and must have the last word.

It was characteristic of Locke's simplicity and intensity that he retained these insulated sympathies in various quarters. A further instance of his many-sidedness was his fidelity to pure intuition, his respect for the infallible revelation of ideal being, such as we have of sensible qualities or of mathematical relations. In dreams and in hallucinations appearances may deceive us, and the objects we think we see may not exist at all. Yet in suffering an illusion we must entertain an idea; and the manifest character of these ideas is that of which alone, Locke thinks, we can have certain "knowledge".

"These", he writes, "are two very different things and carefully to be distinguished: it being one thing to perceive and know the idea of white or black, and quite another to examine what kind of particles they must be, and how arranged ... to make any object appear white or black." "A man infallibly knows, as soon as ever he has them in his mind, that the ideas he calls white and round are the very ideas they are, and that they are not other ideas which he calls red or square.... This ... the mind ... always perceives at first sight; and if ever there happen any doubt about it, it will always be found to be about the names and not the ideas themselves."

This sounds like high Platonic doctrine for a philosopher of the Left; but Locke's utilitarian temper very soon reasserted itself in this subject. Mathematical ideas were not only lucid but true: and he demanded this truth, which he called "reality", of all ideas worthy of consideration: mere ideas would be worthless. Very likely he forgot, in his philosophic puritanism, that fiction and music might have an intrinsic charm. Where the frontier of human wisdom should be drawn in this direction was clearly indicated, in Locke's day, by Spinoza, who says:

"If, in keeping non-existent things present to the imagination, the mind were at the same time aware that those things did not exist, surely it would regard this gift of imagination as a virtue in its own constitution, not as a vice: especially if such an imaginative faculty depended on nothing except the mind's own nature: that is to say, if this mental faculty of imagination were free".

But Locke had not so firm a hold on truth that he could afford to play with fancy; and as he pushed forward the claims of human jurisdiction rather too far in physics, by assuming the current science to be literally true, so, in the realm of imagination, he retrenched somewhat illiberally our legitimate possessions. Strange that as modern philosophy transfers the visible wealth of nature more and more to the mind, the mind should seem to lose courage and to become ashamed of its own fertility. The hard-pressed natural man will not indulge his imagination unless it poses for truth; and being half aware of this imposition, he is more troubled at the thought of being deceived than at the fact of being mechanised or being bored: and he would wish to escape imagination altogether. A good God, he murmurs, could not have made us poets against our will.

Against his will, however, Locke was drawn to enlarge the subjective sphere. The actual existence of mind was evident: you had only to notice the fact that you were thinking. Conscious mind, being thus known to exist directly and independently of the body, was a primary constituent of reality: it was a fact on its own account. Common sense seemed to testify to this, not only when confronted with the "I think, therefore I am" of Descartes, but whenever a thought produced an action. Since mind and body interacted, each must be as real as the other and, as it were, on the same plane of being. Locke, like a good Protestant, felt the right of the conscious inner man to assert himself: and when he looked into his own mind, he found nothing to define this mind except the ideas which occupied it. The existence which he was so sure of in himself was therefore the existence of his ideas.

Here, by an insensible shift in the meaning of the word "idea", a momentous revolution had taken place in psychology. Ideas had originally meant objective terms distinguished in thought-images, qualities, concepts, propositions. But now ideas began to mean living thoughts, moments or states of consciousness. They became atoms of mind, constituents of experience, very much as material atoms were conceived to be constituents of natural objects. Sensations became the only objects of sensation, and ideas the only objects of ideas; so that the material world was rendered superfluous, and the only scientific problem was now to construct a universe in terms of analytic psychology. Locke himself did not go so far, and continued to assign physical causes and physical objects to some, at least, of his mental units; and indeed sensations and ideas could not very well have other than physical causes, the existence of which this new psychology was soon to deny: so that about the origin of its data it was afterwards compelled to preserve a discreet silence. But as to their combinations and reappearances, it was able to invoke the principle of association: a thread on which many shrewd observations may be strung, but which also, when pressed, appears to be nothing but a verbal mask for organic habits in matter.

The fact is that there are two sorts of unobjectionable psychology, neither of which describes a mechanism of disembodied mental states, such as the followers of Locke developed into modern idealism, to the confusion of common sense. One unobjectionable sort of psychology is biological, and studies life from the outside. The other sort, relying on memory and dramatic imagination, reproduces life from the inside, and is literary. If the literary psychologist is a man of genius, by the clearness and range of his memory, by quickness of sympathy and power of suggestion, he may come very near to the truth of experience, as it has been or might be unrolled in a human being. The ideas with which Locke operates are simply high lights picked out by attention in this nebulous continuum, and identified by names. Ideas, in the original ideal sense of the word, are indeed the only definite terms which attention can discriminate and rest upon; but the unity of these units is specious, not existential. If ideas were not logical or aesthetic essences but self-subsisting feelings, each knowing itself, they would be insulated for ever; no spirit could ever survey, recognise, or compare them; and mind would have disappeared in the analysis of mind.

These considerations might enable us, I think, to mark the just frontier of common sense even in this debatable land of psychology. All that is biological, observable, and documentary in psychology falls within the lines of physical science and offers no difficulty in principle. Nor need literary psychology form a dangerous salient in the circuit of nature. The dramatic poet or dramatic historian necessarily retains the presupposition of a material world, since beyond his personal memory (and even within it) he has nothing to stimulate and control his dramatic imagination save knowledge of the material circumstances in which people live, and of the material expression in action or words which they give to their feelings. His moral insight simply vivifies the scene that nature and the sciences of nature spread out before him: they tell him what has happened, and his heart tells him what has been felt. Only literature can describe experience for the excellent reason that the terms of experience are moral and literary from the beginning. Mind is incorrigibly poetical: not because it is not attentive to material facts and practical exigencies, but because, being intensely attentive to them, it turns them into pleasures and pains, and into many-coloured ideas. Yet at every turn there is a possibility and an occasion for transmuting this poetry into science, because ideas and emotions, being caused by material events, refer to these events, and record their order.

All philosophies are frail, in that they are products of the human mind, in which everything is essentially reactive, spontaneous, and volatile: but as in passion and in language, so in philosophy, there are certain comparatively steady and hereditary principles, forming a sort of orthodox reason, which is or which may become the current grammar of mankind. Of philosophers who are orthodox in this sense, only the earliest or the most powerful, an Aristotle or a Spinoza, need to be remembered, in that they stamp their language and temper upon human reason itself. The rest of the orthodox are justly lost in the crowd and relegated to the chorus. The frailty of heretical philosophers is more conspicuous and interesting: it makes up the chronique scandaleuse of the mind, or the history of philosophy. Locke belongs to both camps: he was restive in his orthodoxy and timid in his heresies; and like so many other initiators of revolutions, he would be dismayed at the result of his work. In intention Locke occupied an almost normal philosophic position, rendered precarious not by what was traditional in it, like the categories of substance and power, but rather by certain incidental errors, notably by admitting an experience independent of bodily life, yet compounded and evolving in a mechanical fashion. But I do not find in him a prickly nest of obsolete notions and contradictions from which, fledged at last, we have flown to our present enlightenment. In his person, in his temper, in his allegiances and hopes, he was the prototype of a race of philosophers native and dominant among people of English speech, if not in academic circles, at least in the national mind. If we make allowance for a greater personal subtlety, and for the diffidence and perplexity inevitable in the present moral anarchy of the world, we may find this same Lockian eclecticism and prudence in the late Lord Balfour: and I have myself had the advantage of being the pupil of a gifted successor and, in many ways, emulator, of Locke, I mean William James. So great, at bottom, does their spiritual kinship seem to me to be, that I can hardly conceive Locke vividly without seeing him as a sort of William James of the seventeenth century. And who of you has not known some other spontaneous, inquisitive, unsettled genius, no less preoccupied with the marvellous intelligence of some Brazilian parrot, than with the sad obstinacy of some Bishop of Worcester? Here is eternal freshness of conviction and ardour for reform; great keenness of perception in spots, and in other spots lacunae and impulsive judgments; distrust of tradition, of words, of constructive argument; horror of vested interests and of their smooth defenders; a love of navigating alone and exploring for oneself even the coasts already well charted by others. Here is romanticism united with a scientific conscience and power of destructive analysis balanced by moral enthusiasm. Doubtless Locke might have dug his foundations deeper and integrated his faith better. His system was no metaphysical castle, no theological acropolis: rather a homely ancestral manor house built in several styles of architecture: a Tudor chapel, a Palladian front toward the new geometrical garden, a Jacobean parlour for political consultation and learned disputes, and even since we are almost in the eighteenth century, a Chinese cabinet full of curios. It was a habitable philosophy, and not too inharmonious. There was no greater incongruity in its parts than in the gentle variations of English weather or in the qualified moods and insights of a civilised mind. Impoverished as we are, morally and humanly, we can no longer live in such a rambling mansion. It has become a national monument. On the days when it is open we revisit it with admiration; and those chambers and garden walks re-echo to us the clear dogmas and savoury diction of the sage, omnivorous, artless, loquacious, whose dwelling it was.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Paper read before the Royal Society of Literature on the occasion of the Tercentenary of the birth of John Locke.

George Santayana - 1863, Madrid, Spain - 1952, Rome, Italy