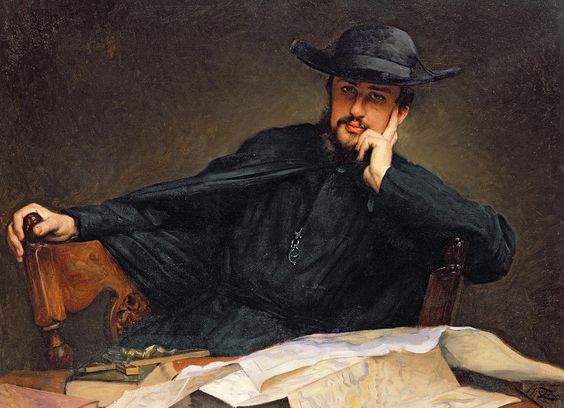

Abbe Marignan's

martial name suited him well. He was a tall, thin priest, fanatic,

excitable, yet upright. All his beliefs were fixed, never varying. He

believed sincerely that he knew his God, understood His plans, desires

and intentions.

When he walked with

long strides along the garden walk of his little country parsonage, he

would sometimes ask himself the question: “Why has God done this?” And

he would dwell on this continually, putting himself in the place of God,

and he almost invariably found an answer. He would never have cried out

in an outburst of pious humility: “Thy ways, O Lord, are past finding

out.”

He said to himself:

“I am the servant of God; it is right for me to know the reason of His

deeds, or to guess it if I do not know it.”

Everything in nature

seemed to him to have been created in accordance with an admirable and

absolute logic. The “whys” and “becauses” always balanced. Dawn was

given to make our awakening pleasant, the days to ripen the harvest, the

rains to moisten it, the evenings for preparation for slumber, and the

dark nights for sleep.

The four seasons

corresponded perfectly to the needs of agriculture, and no suspicion had

ever come to the priest of the fact that nature has no intentions;

that, on the contrary, everything which exists must conform to the hard

demands of seasons, climates and matter.

But he hated woman -

hated her unconsciously, and despised her by instinct. He often

repeated the words of Christ: “Woman, what have I to do with thee ?” and

he would add: “It seems as though God, Himself, were dissatisfied with

this work of His.” She was the tempter who led the first man astray, and

who since then had ever been busy with her work of damnation, the

feeble creature, dangerous and mysteriously affecting one. And even more

than their sinful bodies, he hated their loving hearts.

He had often felt

their tenderness directed toward himself, and though he knew that he was

invulnerable, he grew angry at this need of love that is always

vibrating in them.

According to his

belief, God had created woman for the sole purpose of tempting and

testing man. One must not approach her without defensive precautions and

fear of possible snares. She was, indeed, just like a snare, with her

lips open and her arms stretched out to man.

He had no indulgence

except for nuns, whom their vows had rendered inoffensive; but he was

stern with them, nevertheless, because he felt that at the bottom of

their fettered and humble hearts the everlasting tenderness was burning

brightly, that tenderness which was shown even to him, a priest.

He felt this cursed

tenderness, even in their docility, in the low tones of their voices

when speaking to him, in their lowered eyes, and in their resigned tears

when he reproved them roughly. And he would shake his cassock on

leaving the convent doors, and walk off, lengthening his stride as

though flying from danger.

He had a niece who lived with her mother in a little house near him. He was bent upon making a sister of charity of her.

She was a pretty,

brainless madcap. When the abbe preached she laughed, and when he was

angry with her she would give him a hug, drawing him to her heart, while

he sought unconsciously to release himself from this embrace which

nevertheless filled him with a sweet pleasure, awakening in his depths

the sensation of paternity which slumbers in every man.

Often, when walking

by her side, along the country road, he would speak to her of God, of

his God. She never listened to him, but looked about her at the sky, the

grass and flowers, and one could see the joy of life sparkling in her

eyes. Sometimes she would dart forward to catch some flying creature,

crying out as she brought it back: “Look, uncle, how pretty it is! I

want to hug it!” And this desire to “hug” flies or lilac blossoms

disquieted, angered, and roused the priest, who saw, even in this, the

ineradicable tenderness that is always budding in women's hearts.

Then there came a

day when the sexton's wife, who kept house for Abbe Marignan, told him,

with caution, that his niece had a lover.

Almost suffocated by

the fearful emotion this news roused in him, he stood there, his face

covered with soap, for he was in the act of shaving.

When he had sufficiently recovered to think and speak he cried: “It is not true; you lie, Melanie !”

But the peasant

woman put her hand on her heart, saying: “May our Lord judge me if I

lie, Monsieur le Cure ! I tell you, she goes there every night when your

sister has gone to bed. They meet by the river side; you have only to

go there and see, between ten o'clock and midnight.”

He ceased scraping

his chin, and began to walk up and down impetuously, as he always did

when he was in deep thought. When he began shaving again he cut himself

three times from his nose to his ear.

All day long he was

silent, full of anger and indignation. To his priestly hatred of this

invincible love was added the exasperation of her spiritual father, of

her guardian and pastor, deceived and tricked by a child, and the

selfish emotion shown by parents when their daughter announces that she

has chosen a husband without them, and in spite of them.

After dinner he

tried to read a little, but could not, growing more and, more angry.

When ten o'clock struck he seized his cane, a formidable oak stick,

which he was accustomed to carry in his nocturnal walks when visiting

the sick. And he smiled at the enormous club which he twirled in a

threatening manner in his strong, country fist. Then he raised it

suddenly and, gritting his teeth, brought it down on a chair, the broken

back of which fell over on the floor.

He opened the door

to go out, but stopped on the sill, surprised by the splendid moonlight,

of such brilliance as is seldom seen.

And, as he was

gifted with an emotional nature, one such as had all those poetic

dreamers, the Fathers of the Church, he felt suddenly distracted and

moved by all the grand and serene beauty of this pale night.

In his little

garden, all bathed in soft light, his fruit trees in a row cast on the

ground the shadow of their slender branches, scarcely in full leaf,

while the giant honeysuckle, clinging to the wall of his house, exhaled a

delicious sweetness, filling the warm moonlit atmosphere with a kind of

perfumed soul.

He began to take

long breaths, drinking in the air as drunkards drink wine, and he walked

along slowly, delighted, marveling, almost forgetting his niece.

As soon as he was

outside of the garden, he stopped to gaze upon the plain all flooded

with the caressing light, bathed in that tender, languishing charm of

serene nights. At each moment was heard the short, metallic note of the

cricket, and distant nightingales shook out their scattered notes, their

light, vibrant music that sets one dreaming, without thinking, a music

made for kisses, for the seduction of moonlight.

The abbe walked on

again, his heart failing, though he knew not why. He seemed weakened,

suddenly exhausted; he wanted to sit down, to rest there, to think, to

admire God in His works.

Down yonder,

following the undulations of the little river, a great line of poplars

wound in and out. A fine mist, a white haze through which the moonbeams

passed, silvering it and making it gleam, hung around and above the

mountains, covering all the tortuous course of the water with a kind of

light and transparent cotton.

The priest stopped once again, his soul filled with a growing and irresistible tenderness.

And a doubt, a vague feeling of disquiet came over him; he was asking one of those questions that he sometimes put to himself.

“Why did God make

this ? Since the night is destined for sleep, unconsciousness, repose,

forgetfulness of everything, why make it more charming than day, softer

than dawn or evening ? And why does this seductive planet, more poetic

than the sun, that seems destined, so discreet is it, to illuminate

things too delicate and mysterious for the light of day, make the

darkness so transparent ?

“Why does not the

greatest of feathered songsters sleep like the others ? Why does it pour

forth its voice in the mysterious night ?

“Why this half-veil

cast over the world ? Why these tremblings of the heart, this emotion of

the spirit, this enervation of the body ? Why this display of

enchantments that human beings do not see, since they are lying in their

beds ? For whom is destined this sublime spectacle, this abundance of

poetry cast from heaven to earth ?”

And the abbe could not understand.

But see, out there,

on the edge of the meadow, under the arch of trees bathed in a shining

mist, two figures are walking side by side.

The man was the

taller, and held his arm about his sweetheart's neck and kissed her brow

every little while. They imparted life, all at once, to the placid

landscape in which they were framed as by a heavenly hand. The two

seemed but a single being, the being for whom was destined this calm and

silent night, and they came toward the priest as a living answer, the

response his Master sent to his questionings.

He stood still, his

heart beating, all upset; and it seemed to him that he saw before him

some biblical scene, like the loves of Ruth and Boaz, the accomplishment

of the will of the Lord, in some of those glorious stories of which the

sacred books tell. The verses of the Song of Songs began to ring in his

ears, the appeal of passion, all the poetry of this poem replete with

tenderness.

And he said unto himself: “Perhaps God has made such nights as these to idealize the love of men.”

He shrank back from

this couple that still advanced with arms intertwined. Yet it was his

niece. But he asked himself now if he would not be disobeying God. And

does not God permit love, since He surrounds it with such visible

splendor ?

And he went back musing, almost ashamed, as if he had intruded into a temple where he had, no right to enter.