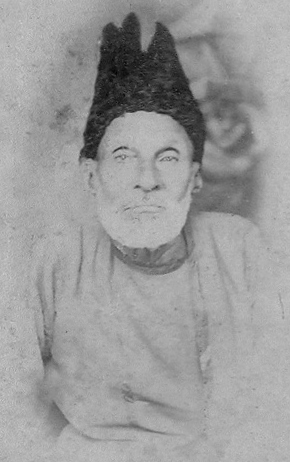

Mirza Asadullah Baig Khan (Urdu/Persian: مرزا اسد اللہ بیگ خان)

was a classical Urdu and Persian poet from India during British colonial

rule. His also known as 'Mirza Asadullah Khan Galib', 'Mirza Galib',

'Dabir-ul-Mulk' and 'Najm-ud-Daula'. His pen-names was Ghaliband Asad or

Asad or Galib. During his lifetime the Mughals were eclipsed and

displaced by the British and finally deposed following the defeat of the

Indian rebellion of 1857, events that he wrote of. Most notably, he

wrote several ghazals during his life, which have since been interpreted

and sung in many different ways by different people. He is considered,

in South Asia, to be one of the most popular and influential poets of

the Urdu language. Ghalib today remains popular not only in India and

Pakistan but also amongst diaspora communities around the world.

Family and Early Life

Mirza Ghalib was born in Agra into a family descended from Aibak Turks who moved to Samarkand after the downfall of the Seljuk kings. His paternal grandfather, Mirza Qoqan Baig Khan was a Saljuq Turk who had immigrated to India from Samarkand (now in Uzbekistan) during the reign of Ahmad Shah (1748–54). He worked at Lahore, Delhi and Jaipur, was awarded the subdistrict of Pahasu (Bulandshahr, UP) and finally settled in Agra, UP, India. He had 4 sons and 3 daughters. Mirza Abdullah Baig Khan and Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan were two of his sons. Mirza Abdullah Baig Khan (Ghalib's father) got married to Izzat-ut-Nisa Begum, and then lived at the house of his father in law. He was employed first by the Nawab of Lucknow and then the Nizam of Hyderabad, Deccan. He died in a battle in 1803 in Alwar and was buried at Rajgarh (Alwar, Rajasthan). Then Ghalib was a little over 5 years of age. He was raised first by his Uncle Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan. Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan (Ghalib's uncle) started taking care of the three orphaned children. He was the governor of Agra under the Marathas. The British appointed him an officer of 400 cavalrymen, fixed his salary at Rs.1700.00 month, and awarded him 2 parganas in Mathura (UP, India). When he died in 1806, the British took away the parganas and fixed his pension as Rs. 10,000 per year, linked to the state of Firozepur Jhirka (Mewat, Haryana). The Nawab of Ferozepur Jhirka reduced the pension to Rs. 3000 per year. Ghalib's share was Rs. 62.50 / month. Ghalib was married at age 13 to Umrao Begum, daughter of Nawab Ilahi Bakhsh (brother of the Nawab of Ferozepur Jhirka). He soon moved to Delhi, along with his younger brother, Mirza Yousuf Khan, who had developed schizophrenia at a young age and later died in Delhi during the chaos of 1857.

In accordance with upper class Muslim tradition, he had an arranged marriage at the age of 13, but none of his seven children survived beyond infancy. After his marriage he settled in Delhi. In one of his letters he describes his marriage as the second imprisonment after the initial confinement that was life itself. The idea that life is one continuous painful struggle which can end only when life itself ends, is a recurring theme in his poetry. One of his couplets puts it in a nutshell:

"The prison of life and the bondage of grief are one and the same

Before the onset of death, how can man expect to be free of grief ?"

Royal Titles

In 1850, Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II revived upon Mirza Ghalib the title of "Dabeer-ul-Mulk". The Emperor also added to it the additional title of Najm-ud-daulah.The conferment of these titles was symbolic of Mirza Ghalib’s incorporation into the nobility of Delhi. He also received the title of 'Mirza Nosha' by the emperor, thus adding Mirza as his first name. He was also an important courtier of the royal court of the Emperor. As the Emperor was himself a poet, Mirza Ghalib was appointed as his poet tutor in 1854. He was also appointed as tutor of Prince Fakhr-ud Din Mirza, eldest son of Bahadur Shah II,(d. 10 July 1856). He was also appointed by the Emperor as the royal historian of Mughal Court.

Being a member of declining Mughal nobility and old landed aristocracy, he never worked for a livelihood, lived on either royal patronage of Mughal Emperors, credit or the generosity of his friends. His fame came to him posthumously. He had himself remarked during his lifetime that although his age had ignored his greatness, it would be recognized by later generations. After the decline of Mughal Empire and rise of British Raj, despite his many attempts, Ghalib could never get the full pension restored.

Poetry Career

Ghalib started composing poetry at the age of 11. His first language was Urdu, but Persian and Turkish were also spoken at home. He got his education in Persian and Arabic at a young age. When Ghalib was in his early teens, a newly converted Muslim tourist from Iran (Abdus Samad, originally named Hormuzd, a Zoroastrian) came to Agra. He stayed at Ghalibs home for 2 years. He was a highly educated individual and Ghalib learned Persian, Arabic, philosophy, and logic from him.

Although Ghalib himself was far prouder of his poetic achievements in Persian, he is today more famous for his Urdu ghazals. Numerous elucidations of Ghalib's ghazal compilations have been written by Urdu scholars. The first such elucidation or Sharh was written by Ali Haider Nazm Tabatabai of Hyderabad during the rule of the last Nizam of Hyderabad. Before Ghalib, the ghazal was primarily an expression of anguished love; but Ghalib expressed philosophy, the travails and mysteries of life and wrote ghazals on many other subjects, vastly expanding the scope of the ghazal. This work is considered his paramount contribution to Urdu poetry and literature.

In keeping with the conventions of the classical ghazal, in most of Ghalib's verses, the identity and the gender of the beloved is indeterminate. The critic/poet/writer Shamsur Rahman Faruqui explains that the convention of having the "idea" of a lover or beloved instead of an actual lover/beloved freed the poet-protagonist-lover from the demands of realism. Love poetry in Urdu from the last quarter of the seventeenth century onwards consists mostly of "poems about love" and not "love poems" in the Western sense of the term.

The first complete English translation of Ghalib's ghazals was written by Sarfaraz K. Niazi and published by Rupa & Co in India and Ferozsons in Pakistan. The title of this book is Love Sonnets of Ghalib and it contains complete Roman transliteration, explication and an extensive lexicon.

His Letters

Mirza Ghalib was a gifted letter writer. Not only Urdu poetry but the prose is also indebted to Mirza Ghalib. His letters gave foundation to easy and popular Urdu. Before Ghalib, letter writing in Urdu was highly ornamental. He made his letters "talk" by using words and sentences as if he were conversing with the reader. According to him Sau kos se ba-zaban-e-qalam baatein kiya karo aur hijr mein visaal ke maze liya karo (from hundred of miles talk with the tongue of the pen and enjoy the joy of meeting even when you are separated). His letters were very informal, some times he would just write the name of the person and start the letter. He himself was very humorous and also made his letter very interesting. He said Main koshish karta hoon keh koi aesi baat likhoon jo parhay khoosh ho jaaye (I want to write the lines that whoever reads those should enjoy it). When the third wife of one of his friends died, he wrote. Some scholar says that Ghalib would have the same place in Urdu literature if only on the basis of his letters. They have been translated into English by Ralph Russell, The Oxford Ghalib.

Ghalib was a chronicler of this turbulent period. One by one, Ghalib saw the bazaars – Khas Bazaar, Urdu Bazaar, Kharam-ka Bazaar, disappear, whole mohallas (localities) and katras (lanes) vanish. The havelis (mansions) of his friends were razed to the ground. Ghalib wrote that Delhi had become a desert. Water was scarce. Delhi was now “ a military camp”. It was the end of the feudal elite to which Ghalib had belonged. He wrote:

“An ocean of blood churns around me-

Alas ! Were these all !

The future will show

What more remains for me to see”.

His Pen Name

His original Takhallus (pen-name) was Asad, drawn from his given name, Asadullah Khan. At some point early in his poetic career he also decided to adopt the Takhallus Ghalib (meaning all conquering, superior, most excellent).

Popular legend has it that he changed his pen name to 'Ghalib' when he came across this sher (couplet) by another poet who used the takhallus (pen name) 'Asad':

The legend says that upon hearing this couplet, Ghalib ruefully exclaimed, "whoever authored this couplet does indeed deserve the Lord's rahmat (mercy) (for having composed such a deplorable specimen of Urdu poetry). If I use the takhallus Asad, then surely (people will mistake this couplet to be mine and) there will be much la'anat (curse) on me!" And, saying so, he changed his takhallus to 'Ghalib'.

However, this legend is little more than a figment of the legend-creator's imagination. Extensive research performed by commentators and scholars of Ghalib's works, notably Imtiyaz Ali Arshi and Kalidas Gupta Raza, has succeeded in identifying the chronology of Ghalib's published work (sometimes down to the exact calendar day!). Although the takhallus 'Asad' appears more infrequently in Ghalib's work than 'Ghalib', it appears that he did use both his noms de plume interchangeably throughout his career and did not seem to prefer either one over the other.

Mirza Ghalib and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan

1855, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan finished his highly scholarly, very well researched and illustrated edition of Abul Fazl’s Ai’n-e Akbari, itself an extraordinarily difficult book. Having finished the work to his satisfaction, and believing that Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was a person who would appreciate his labours, Syed Ahmad approached the great Ghalib to write a taqriz (in the convention of the times, a laudatory foreword) for it. Ghalib obliged, but what he did produce was a short Persian poem castigating the Ai’n-e Akbari, and by implication, the imperial, sumptuous, literate and learned Mughal culture of which it was a product. The least that could be said against it was that the book had little value even as an antique document. Ghalib practically reprimanded Syed Ahmad Khan for wasting his talents and time on dead things. Worse, he praised sky-high the “Sahibs of England” who at that time held all the keys to all the a’ins in this world.

This poem is often referred to but has never translated in English. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi wrote an English translation.

The poem was unexpected, but it came at the time when Syed Ahmad Khan’s thought and feelings themselves were inclining toward change. Ghalib seemed to be acutely aware of a European[English]-sponsored change in world polity, especially Indian polity. Syed Ahmad might well have been piqued at Ghalib’s admonitions, but he would also have realized that Ghalib’s reading of the situation, though not nuanced enough, was basically accurate. Syed Ahmad Khan may also have felt that he, being better informed about the English and the outside world, should have himself seen the change that now seemed to be just round the corner. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan never again wrote a word in praise of the Ai’n-e Akbari and in fact gave up taking active interest in history and archaeology, and became a social reformer.

Personal Life

Mirza was born in Kala Mahal in Agra. In the end of 18th century, his birthplace was converted into Indrabhan Girls' Inter College. The birth room of Mirza Ghalib is preserved within the school. Around 1810, he was married to Umrao Begum, daughter of Nawab Ilahi Bakhsh Khan of Loharu (younger brother of the first Nawab of Loharu, Nawab Mirza Ahmad Baksh Khan, at the age of thirteen. He had seven children, none of whom survived (this pain has found its echo in some of Ghalib's ghazals). There are conflicting reports regarding his relationship with his wife. She was considered to be pious, conservative and God-fearing. Ghalib was proud of his reputation as a rake. He was once imprisoned for gambling and subsequently relished the affair with pride. In the Mughal court circles, he even acquired a reputation as a "ladies man". Once, when someone praised the poetry of the pious Sheikh Sahbai in his presence, Ghalib immediately retorted:

“How can Sahbai be a poet? He has never tasted wine, nor has he ever gambled; he has not been beaten with slippers by lovers, nor has he ever seen the inside of a jail."

He died in Delhi on February 15, 1869. The house where he lived in Gali Qasim Jaan, Ballimaran, Chandni Chowk, in Old Delhi has now been turned into 'Ghalib Memorial' and houses a permanent Ghalib exhibition.

Religious Views

Ghalib was a very liberal mystic who believed that the search for God within liberated the seeker from the narrowly Orthodox Islam, encouraging the devotee to look beyond the letter of the law to its narrow essence. His Sufi views and mysticism is greatly reflected in his poems and ghazals. As he once stated:

“The object of my worship lies beyond perception's reach;

For men who see, the Ka'aba is a compass, nothing more."

Like many other Urdu poets, Ghalib was capable of writing profoundly religious poetry, yet was skeptical about the literalist interpretation of the Islamic scriptures. On the Islamic view and claims of paradise, he once wrote in a letter to a friend:

“In paradise it is true that I shall drink at dawn the pure wine mentioned in the Qu'ran, but where in paradise are the long walks with intoxicated friends in the night, or the drunken crowds shouting merrily? Where shall I find there the intoxication of Monsoon clouds? Where there is no autumn, how can spring exist? If the beautiful houris are always there, where will be the sadness of separation and the joy of union? Where shall we find there a girl who flees away when we would kiss her?”

He staunchly disdained the Orthodox Muslim Sheikhs of the Ulema, who in his poems always represent narrow-mindedness and hypocrisy:

“The Sheikh hovers by the tavern door,

but believe me, Ghalib,

I am sure I saw him slip in

As I departed."

In another verse directed towards the Muslim maulavis (clerics), he criticized them for their ignorance and arrogant certitude: "Look deeper, it is you alone who cannot hear the music of his secrets". In his letters, Ghalib frequently contrasted the narrow legalism of the Ulema with "it's pre-occupation with teaching the baniyas and the brats, and wallowing in the problems of menstruation and menstrual bleeding" and real spirituality for which you had to "study the works of the mystics and take into one's heart the essential truth of God's reality and his expression in all things".

Ghalib believed that if God laid within and could be reached less by ritual than by love, then he was as accessible to Hindus as to Muslims. As a testament to this, he would later playfully write in a letter that during a trip to Benares, he was half tempted to settle down there for good and that he wished he had renounced Islam, put a Hindu sectarian mark on his forehead, tied a sectarian thread around his waist and seated himself on the banks of the Ganges so that he could wash the contamination of his existence away from himself and like a drop be one with the river.

During the anti-British Rebellion in Delhi on 5 October 1857, three weeks after the British troops had entered through Kashmiri Gate, some soldiers climbed into Ghalib's neighbourhood and hauled him off to Colonel Burn for questioning. He appeared in front of the colonel wearing a Turkish style headdress. The colonel, bemused at his appearance, inquired in broken Urdu, "Well ? You Muslim ?", to which Ghalib replied, "Half ?" The colonel asked, "What does that mean ?" In response, Ghalib said, "I drink wine, but I don't eat pork."

Views on Hindustan

In his poem "Chirag-i-Dair" (Temple lamps) which was composed during his trip to Benaras during the spring of 1827, Ghalib mused about the land of Hindustan (the Indian subcontinent) and how Qiyamah (Doomsday) has failed to arrive, in spite of the numerous conflicts plaguing it.

“Said I one night to a pristine seer

(Who knew the secrets of whirling time)

"Sir, you well perceive

That goodness and faith,

Fidelity and love

Have all departed from this sorry land

Father and son are at each other's throat;

Brother fights brother, Unity and federation are undermined

Despite all these ominous signs, Why has not Doomsday come ?

Who holds the reins of the Final Catastrophe ?

The hoary old man of lucent ken

Pointed towards Kashi and gently smiled

"The Architect", he said, "is fond of this edifice

Because of which there is color in life; He

Would not like it to perish and fall."

Contemporaries and Disciples

Ghalib's closest rival was poet Zauq, tutor of Bahadur Shah Zafar II, the then emperor of India with his seat in Delhi. There are some amusing anecdotes of the competition between Ghalib and Zauq and exchange of jibes between them. However, there was mutual respect for each other's talent. Both also admired and acknowledged the supremacy of Meer Taqi Meer, a towering figure of 18th century Urdu Poetry. Another poet Momin, whose ghazals had a distinctly lyrical flavour, was also a famous contemporary of Ghalib. Ghalib was not only a poet, he was also a prolific prose writer. His letters are a reflection of the political and social climate of the time. They also refer to many contemporaries like Mir Mehdi Majrooh, who himself was a good poet and Ghalib's life-long acquaintance.

Mirza Ghalib's Works:

Urdu Letters of Mirza Asadullah Khan Galib, Translated by Daud Rahbar, SUNY Press, 1987.

Family and Early Life

Mirza Ghalib was born in Agra into a family descended from Aibak Turks who moved to Samarkand after the downfall of the Seljuk kings. His paternal grandfather, Mirza Qoqan Baig Khan was a Saljuq Turk who had immigrated to India from Samarkand (now in Uzbekistan) during the reign of Ahmad Shah (1748–54). He worked at Lahore, Delhi and Jaipur, was awarded the subdistrict of Pahasu (Bulandshahr, UP) and finally settled in Agra, UP, India. He had 4 sons and 3 daughters. Mirza Abdullah Baig Khan and Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan were two of his sons. Mirza Abdullah Baig Khan (Ghalib's father) got married to Izzat-ut-Nisa Begum, and then lived at the house of his father in law. He was employed first by the Nawab of Lucknow and then the Nizam of Hyderabad, Deccan. He died in a battle in 1803 in Alwar and was buried at Rajgarh (Alwar, Rajasthan). Then Ghalib was a little over 5 years of age. He was raised first by his Uncle Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan. Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan (Ghalib's uncle) started taking care of the three orphaned children. He was the governor of Agra under the Marathas. The British appointed him an officer of 400 cavalrymen, fixed his salary at Rs.1700.00 month, and awarded him 2 parganas in Mathura (UP, India). When he died in 1806, the British took away the parganas and fixed his pension as Rs. 10,000 per year, linked to the state of Firozepur Jhirka (Mewat, Haryana). The Nawab of Ferozepur Jhirka reduced the pension to Rs. 3000 per year. Ghalib's share was Rs. 62.50 / month. Ghalib was married at age 13 to Umrao Begum, daughter of Nawab Ilahi Bakhsh (brother of the Nawab of Ferozepur Jhirka). He soon moved to Delhi, along with his younger brother, Mirza Yousuf Khan, who had developed schizophrenia at a young age and later died in Delhi during the chaos of 1857.

In accordance with upper class Muslim tradition, he had an arranged marriage at the age of 13, but none of his seven children survived beyond infancy. After his marriage he settled in Delhi. In one of his letters he describes his marriage as the second imprisonment after the initial confinement that was life itself. The idea that life is one continuous painful struggle which can end only when life itself ends, is a recurring theme in his poetry. One of his couplets puts it in a nutshell:

"The prison of life and the bondage of grief are one and the same

Before the onset of death, how can man expect to be free of grief ?"

Royal Titles

In 1850, Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II revived upon Mirza Ghalib the title of "Dabeer-ul-Mulk". The Emperor also added to it the additional title of Najm-ud-daulah.The conferment of these titles was symbolic of Mirza Ghalib’s incorporation into the nobility of Delhi. He also received the title of 'Mirza Nosha' by the emperor, thus adding Mirza as his first name. He was also an important courtier of the royal court of the Emperor. As the Emperor was himself a poet, Mirza Ghalib was appointed as his poet tutor in 1854. He was also appointed as tutor of Prince Fakhr-ud Din Mirza, eldest son of Bahadur Shah II,(d. 10 July 1856). He was also appointed by the Emperor as the royal historian of Mughal Court.

Being a member of declining Mughal nobility and old landed aristocracy, he never worked for a livelihood, lived on either royal patronage of Mughal Emperors, credit or the generosity of his friends. His fame came to him posthumously. He had himself remarked during his lifetime that although his age had ignored his greatness, it would be recognized by later generations. After the decline of Mughal Empire and rise of British Raj, despite his many attempts, Ghalib could never get the full pension restored.

Poetry Career

Ghalib started composing poetry at the age of 11. His first language was Urdu, but Persian and Turkish were also spoken at home. He got his education in Persian and Arabic at a young age. When Ghalib was in his early teens, a newly converted Muslim tourist from Iran (Abdus Samad, originally named Hormuzd, a Zoroastrian) came to Agra. He stayed at Ghalibs home for 2 years. He was a highly educated individual and Ghalib learned Persian, Arabic, philosophy, and logic from him.

Although Ghalib himself was far prouder of his poetic achievements in Persian, he is today more famous for his Urdu ghazals. Numerous elucidations of Ghalib's ghazal compilations have been written by Urdu scholars. The first such elucidation or Sharh was written by Ali Haider Nazm Tabatabai of Hyderabad during the rule of the last Nizam of Hyderabad. Before Ghalib, the ghazal was primarily an expression of anguished love; but Ghalib expressed philosophy, the travails and mysteries of life and wrote ghazals on many other subjects, vastly expanding the scope of the ghazal. This work is considered his paramount contribution to Urdu poetry and literature.

In keeping with the conventions of the classical ghazal, in most of Ghalib's verses, the identity and the gender of the beloved is indeterminate. The critic/poet/writer Shamsur Rahman Faruqui explains that the convention of having the "idea" of a lover or beloved instead of an actual lover/beloved freed the poet-protagonist-lover from the demands of realism. Love poetry in Urdu from the last quarter of the seventeenth century onwards consists mostly of "poems about love" and not "love poems" in the Western sense of the term.

The first complete English translation of Ghalib's ghazals was written by Sarfaraz K. Niazi and published by Rupa & Co in India and Ferozsons in Pakistan. The title of this book is Love Sonnets of Ghalib and it contains complete Roman transliteration, explication and an extensive lexicon.

His Letters

Mirza Ghalib was a gifted letter writer. Not only Urdu poetry but the prose is also indebted to Mirza Ghalib. His letters gave foundation to easy and popular Urdu. Before Ghalib, letter writing in Urdu was highly ornamental. He made his letters "talk" by using words and sentences as if he were conversing with the reader. According to him Sau kos se ba-zaban-e-qalam baatein kiya karo aur hijr mein visaal ke maze liya karo (from hundred of miles talk with the tongue of the pen and enjoy the joy of meeting even when you are separated). His letters were very informal, some times he would just write the name of the person and start the letter. He himself was very humorous and also made his letter very interesting. He said Main koshish karta hoon keh koi aesi baat likhoon jo parhay khoosh ho jaaye (I want to write the lines that whoever reads those should enjoy it). When the third wife of one of his friends died, he wrote. Some scholar says that Ghalib would have the same place in Urdu literature if only on the basis of his letters. They have been translated into English by Ralph Russell, The Oxford Ghalib.

Ghalib was a chronicler of this turbulent period. One by one, Ghalib saw the bazaars – Khas Bazaar, Urdu Bazaar, Kharam-ka Bazaar, disappear, whole mohallas (localities) and katras (lanes) vanish. The havelis (mansions) of his friends were razed to the ground. Ghalib wrote that Delhi had become a desert. Water was scarce. Delhi was now “ a military camp”. It was the end of the feudal elite to which Ghalib had belonged. He wrote:

“An ocean of blood churns around me-

Alas ! Were these all !

The future will show

What more remains for me to see”.

His Pen Name

His original Takhallus (pen-name) was Asad, drawn from his given name, Asadullah Khan. At some point early in his poetic career he also decided to adopt the Takhallus Ghalib (meaning all conquering, superior, most excellent).

Popular legend has it that he changed his pen name to 'Ghalib' when he came across this sher (couplet) by another poet who used the takhallus (pen name) 'Asad':

The legend says that upon hearing this couplet, Ghalib ruefully exclaimed, "whoever authored this couplet does indeed deserve the Lord's rahmat (mercy) (for having composed such a deplorable specimen of Urdu poetry). If I use the takhallus Asad, then surely (people will mistake this couplet to be mine and) there will be much la'anat (curse) on me!" And, saying so, he changed his takhallus to 'Ghalib'.

However, this legend is little more than a figment of the legend-creator's imagination. Extensive research performed by commentators and scholars of Ghalib's works, notably Imtiyaz Ali Arshi and Kalidas Gupta Raza, has succeeded in identifying the chronology of Ghalib's published work (sometimes down to the exact calendar day!). Although the takhallus 'Asad' appears more infrequently in Ghalib's work than 'Ghalib', it appears that he did use both his noms de plume interchangeably throughout his career and did not seem to prefer either one over the other.

Mirza Ghalib and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan

1855, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan finished his highly scholarly, very well researched and illustrated edition of Abul Fazl’s Ai’n-e Akbari, itself an extraordinarily difficult book. Having finished the work to his satisfaction, and believing that Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib was a person who would appreciate his labours, Syed Ahmad approached the great Ghalib to write a taqriz (in the convention of the times, a laudatory foreword) for it. Ghalib obliged, but what he did produce was a short Persian poem castigating the Ai’n-e Akbari, and by implication, the imperial, sumptuous, literate and learned Mughal culture of which it was a product. The least that could be said against it was that the book had little value even as an antique document. Ghalib practically reprimanded Syed Ahmad Khan for wasting his talents and time on dead things. Worse, he praised sky-high the “Sahibs of England” who at that time held all the keys to all the a’ins in this world.

This poem is often referred to but has never translated in English. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi wrote an English translation.

The poem was unexpected, but it came at the time when Syed Ahmad Khan’s thought and feelings themselves were inclining toward change. Ghalib seemed to be acutely aware of a European[English]-sponsored change in world polity, especially Indian polity. Syed Ahmad might well have been piqued at Ghalib’s admonitions, but he would also have realized that Ghalib’s reading of the situation, though not nuanced enough, was basically accurate. Syed Ahmad Khan may also have felt that he, being better informed about the English and the outside world, should have himself seen the change that now seemed to be just round the corner. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan never again wrote a word in praise of the Ai’n-e Akbari and in fact gave up taking active interest in history and archaeology, and became a social reformer.

Personal Life

Mirza was born in Kala Mahal in Agra. In the end of 18th century, his birthplace was converted into Indrabhan Girls' Inter College. The birth room of Mirza Ghalib is preserved within the school. Around 1810, he was married to Umrao Begum, daughter of Nawab Ilahi Bakhsh Khan of Loharu (younger brother of the first Nawab of Loharu, Nawab Mirza Ahmad Baksh Khan, at the age of thirteen. He had seven children, none of whom survived (this pain has found its echo in some of Ghalib's ghazals). There are conflicting reports regarding his relationship with his wife. She was considered to be pious, conservative and God-fearing. Ghalib was proud of his reputation as a rake. He was once imprisoned for gambling and subsequently relished the affair with pride. In the Mughal court circles, he even acquired a reputation as a "ladies man". Once, when someone praised the poetry of the pious Sheikh Sahbai in his presence, Ghalib immediately retorted:

“How can Sahbai be a poet? He has never tasted wine, nor has he ever gambled; he has not been beaten with slippers by lovers, nor has he ever seen the inside of a jail."

He died in Delhi on February 15, 1869. The house where he lived in Gali Qasim Jaan, Ballimaran, Chandni Chowk, in Old Delhi has now been turned into 'Ghalib Memorial' and houses a permanent Ghalib exhibition.

Religious Views

Ghalib was a very liberal mystic who believed that the search for God within liberated the seeker from the narrowly Orthodox Islam, encouraging the devotee to look beyond the letter of the law to its narrow essence. His Sufi views and mysticism is greatly reflected in his poems and ghazals. As he once stated:

“The object of my worship lies beyond perception's reach;

For men who see, the Ka'aba is a compass, nothing more."

Like many other Urdu poets, Ghalib was capable of writing profoundly religious poetry, yet was skeptical about the literalist interpretation of the Islamic scriptures. On the Islamic view and claims of paradise, he once wrote in a letter to a friend:

“In paradise it is true that I shall drink at dawn the pure wine mentioned in the Qu'ran, but where in paradise are the long walks with intoxicated friends in the night, or the drunken crowds shouting merrily? Where shall I find there the intoxication of Monsoon clouds? Where there is no autumn, how can spring exist? If the beautiful houris are always there, where will be the sadness of separation and the joy of union? Where shall we find there a girl who flees away when we would kiss her?”

He staunchly disdained the Orthodox Muslim Sheikhs of the Ulema, who in his poems always represent narrow-mindedness and hypocrisy:

“The Sheikh hovers by the tavern door,

but believe me, Ghalib,

I am sure I saw him slip in

As I departed."

In another verse directed towards the Muslim maulavis (clerics), he criticized them for their ignorance and arrogant certitude: "Look deeper, it is you alone who cannot hear the music of his secrets". In his letters, Ghalib frequently contrasted the narrow legalism of the Ulema with "it's pre-occupation with teaching the baniyas and the brats, and wallowing in the problems of menstruation and menstrual bleeding" and real spirituality for which you had to "study the works of the mystics and take into one's heart the essential truth of God's reality and his expression in all things".

Ghalib believed that if God laid within and could be reached less by ritual than by love, then he was as accessible to Hindus as to Muslims. As a testament to this, he would later playfully write in a letter that during a trip to Benares, he was half tempted to settle down there for good and that he wished he had renounced Islam, put a Hindu sectarian mark on his forehead, tied a sectarian thread around his waist and seated himself on the banks of the Ganges so that he could wash the contamination of his existence away from himself and like a drop be one with the river.

During the anti-British Rebellion in Delhi on 5 October 1857, three weeks after the British troops had entered through Kashmiri Gate, some soldiers climbed into Ghalib's neighbourhood and hauled him off to Colonel Burn for questioning. He appeared in front of the colonel wearing a Turkish style headdress. The colonel, bemused at his appearance, inquired in broken Urdu, "Well ? You Muslim ?", to which Ghalib replied, "Half ?" The colonel asked, "What does that mean ?" In response, Ghalib said, "I drink wine, but I don't eat pork."

Views on Hindustan

In his poem "Chirag-i-Dair" (Temple lamps) which was composed during his trip to Benaras during the spring of 1827, Ghalib mused about the land of Hindustan (the Indian subcontinent) and how Qiyamah (Doomsday) has failed to arrive, in spite of the numerous conflicts plaguing it.

“Said I one night to a pristine seer

(Who knew the secrets of whirling time)

"Sir, you well perceive

That goodness and faith,

Fidelity and love

Have all departed from this sorry land

Father and son are at each other's throat;

Brother fights brother, Unity and federation are undermined

Despite all these ominous signs, Why has not Doomsday come ?

Who holds the reins of the Final Catastrophe ?

The hoary old man of lucent ken

Pointed towards Kashi and gently smiled

"The Architect", he said, "is fond of this edifice

Because of which there is color in life; He

Would not like it to perish and fall."

Contemporaries and Disciples

Ghalib's closest rival was poet Zauq, tutor of Bahadur Shah Zafar II, the then emperor of India with his seat in Delhi. There are some amusing anecdotes of the competition between Ghalib and Zauq and exchange of jibes between them. However, there was mutual respect for each other's talent. Both also admired and acknowledged the supremacy of Meer Taqi Meer, a towering figure of 18th century Urdu Poetry. Another poet Momin, whose ghazals had a distinctly lyrical flavour, was also a famous contemporary of Ghalib. Ghalib was not only a poet, he was also a prolific prose writer. His letters are a reflection of the political and social climate of the time. They also refer to many contemporaries like Mir Mehdi Majrooh, who himself was a good poet and Ghalib's life-long acquaintance.

Mirza Ghalib's Works:

Urdu Letters of Mirza Asadullah Khan Galib, Translated by Daud Rahbar, SUNY Press, 1987.

http://www.poemhunter.com/mirza-ghalib/biography/

POETRY

About My Poems

I agree, O heart, that my ghazals are not easy to take in.

When they hear my works, experienced poets

tell meI should write something easier.

I have to write difficult, otherwise it is difficult to write.

I have seen almost all the possible Troubles in my life

I have seen almost all the possible Troubles in my life,

The last one that I have to face is the Death.

I Will Not Cry

I will not cry for satisfaction if I could get my choice,

Among the divine beautiful virgins of heaven, I want only you.

After killing me, do not bury me in your street,

Why should people know your home address with my reference.

Be chivalrous for you are the wine bearer (beloved) , or else I

use to drink as much wine as I get every night.

I have no business with you but O! dear friend,

Convey my regards to the postman if you see him,

(to remind him that he has to deliver my message to my beloved) .

I will show you what Majnoo (Hero of the famous Arabic love tale, Layla Majnoo) did,

If I could spare some time of my inner grief.

I am not bound to follow the directions given by Khizar

(A prophet who is believed to be still alive and guide the people, who have lost their way, to the right path) ,

I accept that he remained my companion during my journey.

O ! The inhabitants of the street of my beloved see

if you could find the insane poet Ghalib there some where.

Come that my soul has no repose

Come that my soul has no repose

Has no strength to bear the injustice of waiting

Heaven is given in return for the life of this world

But that high is not in proportion to this intoxication

Such longing has come from your company

That there is no control over my tears

Suspecting torment, you are indifferent to me

So no love resides in these clouds of dust

From my heart has lifted the meaning of pleasure

Without blossoms, there is no spring in life

You have pledged to kill me at last

But there is no determination in your promise

You have sworn by the wine, Ghalib

There is no faith in your avowal

Innocent heart

Innocent heart, what has happened to you ?

Alas, what is the cure to this pain ?

We are interested, and they are displeased,

Oh Lord, what is this affair ?

I too possess a tongue-

just ask me what I want to say.

Though there is none present without you,

then oh God, what is this noise about ?

I expected faith from those

who do not even know what faith is.

Kiss Me

Ghooncha-e-nashiguftha ko dhoor se math dikha key yoon

Bosey ko poonchtha houn mein munh se muchey batha ki yoon

Translation:

Don't stay afar pouting your lips at me like a rosebud;

I asked you for a kiss--let your lips answer my plea.

No Hope Comes My Way

No hope comes my way

No visage shows itself to me

That death will come one day is definite

Then why does sleep evade me all night ?

I used to laugh at the state of my heart

Now no one thing brings a smile

Though I know the reward of religious devotion

My attention does not settle in that direction

It is for these reasons that I am quiet

If not, would I not converse with you ?

Why should I not remember you ?

Even if you cannot hear my lament

You don't see the anguish in my heart

O healer, the scent of my pain eludes you

I am now at that point

That even I don't know myself

I die in the hope of dying

Death arrives and then never arrives

How will you face Mecca, Ghalib

When shame doesn't come to you

Pain did not become grateful to medicine

Pain did not become grateful to medicine

I didn't get well; [but it] wasn't bad either

Why are you gathering the Rivals ?

[It was just] a mere spectacle [that] took place, no complaint was made

Where would we go to test our fate/ destiny ?

When you yourself did not put your dagger to test

How sweet are your lips, that the rival

[after] receiving abuse, did not lack pleasure

Recent/ hot news is that she is coming

Only today, in the house there was not a straw mat !

Does the divinity belonged to Namrood' ?

[cause] in your servitude, my wellbeing did not happen

[God] gave life- the given [life] was His alone

The truth is; that the responsibility was not fulfilled [by us]

If the wound was pressed, the blood did not stop

[though] the task was halted, [but the bleeding still] set out

Is it highway robbery, or is it heart-theft ?

Having taken the heart, the heart-thief set out [to depart]

Recite something, for people are saying

Today "Ghalib" was not a ghazal-reciter

The dropp dies in the river

The dropp dies in the riverof its joy

Pain goes so far it cures itself

In the spring after the heavy rain the cloud disappears

That was nothing but tears

In the spring the mirror turns green

holding a miracle

Change the shining wind

The rose led us to our eyes

Let whatever is be open.

(Translated by W. S. Merwin and Aijaz Ahmed)

This Was Not Our Destiny

This was not our destiny, that union with the beloved would take place.

If we had kept on living longer, then would have been kept waiting

If I lived on your promise, then know this that I knew it to be false

For would I not have died of happiness, if I had had trust [in it] ?

From your delicacy I knew that the vow had been bound loosely

You could never have broken it, if it had been firm

Let someone ask my heart about your half-drawn arrow

Where would this anxiety/ pain have come from, if it had gone through the liver ?

What kind of friendship is this, that friends have become Advisors ?

If someone had been a healer, if someone had been a sympathizer !

From the rock-vein would drip that blood which would never have stopped

If this which you are considering 'grief' this were just a spark

Although grief is life-threatening, how would we escape, while there is a heart ?

If there were not the grief of passion, there would be the grief of livelihood

To whom might I say what it is- the night of sadness is a bad disaster!

Why would I have minded dying, if it took place one time?

Since upon having died, I became disgraced- why were I not drowned in the ocean?

Neither a funeral procession would ever been formed, nor would there anywhere be a tomb

Who can see him? for that Oneness is unique

If there were even a whiff of twoness, then somehow [He] would be two or four

These problems of mysticism! this discourse of yours, Ghalib !

We would consider you a saint- if you weren't a wine-drinker.

What Cannot Be Said

There's one who took my heart away.

But does she own it ? I can't say.

See her as unjust though I may,

Is she a tyrant ? I can't say.

She strides a bloodless battlefield

Where there's no battle-axe to wield.

She keeps a wineless banquet-hall

Where there's no bowl to raise at all.

Although she serves wine ceaselessly,

Her fingers bring no cup to me.

Her idol-carving hand is sure,

But you cannot call her Azer

When riots quiet down, why must

You brag of ousting the unjust ?

There will be nothing you can say

Of the unjust on Judgment Day.

Within the breast the secret lies

Which none can ever sermonize.

How strange a thing it is that throws

The mind askew till no one knows

How I Ghalib am no believer

But can't be called unfaithful either.

Note:

Azer: in the Islamic tradition, Abraham's father who manufactured and served Nimrod's idols. Known as Terah in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

[Trasnlated from Persian ]